China’s Policymakers Face Big Choices After No Emissions Growth for 18 Months [Op-Ed]

Photo: Shutterstock / chinasong

01 December 2025 – by Lauri Myllyvirta

In a major turnaround, China’s CO2 emissions have been stable or declining for the past 18 months, up to September. As China’s growing fossil fuel consumption has been a key driver of global demand for fossil fuels and the resulting CO2 emissions, this trend could upend global emission trends and fossil fuel markets, as well as China’s own climate and energy policies.

China’s fossil CO2 emissions increased by 25% from 2015 to 2024, contributing 75% of the global emissions increase over the period. Now the country’s clean energy boom has sufficed to stop emissions from growing. There have been brief periods of reduced emissions before. Still, they have always been associated with slumping demand – this is the first time that energy demand growth at or above average rates doesn’t result in rising emissions.

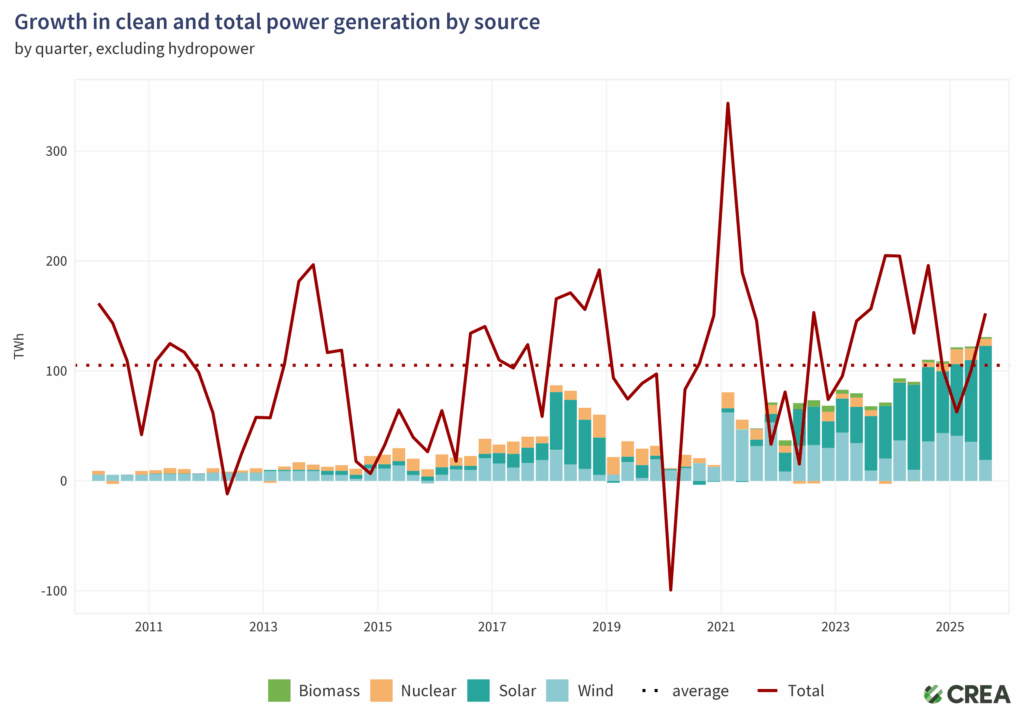

The scale of clean energy additions required to achieve this is staggering. China’s power generation from wind and solar was four times as large as Germany’s total electricity consumption last year. At the growth rates of the first three quarters, the country is on track to add more than another Germany’s worth of power generation from the two technologies this year. Most importantly, this growth rate, if sustained, will be sufficient to meet electricity demand growth and reduce fossil fuel use in the power sector.

Progress is equally rapid in the transportation sector, where the rapid adoption of EVs and investment in rail transport have driven down the sector’s CO2 emissions by 5% year-on-year in the first three quarters of 2025. Reductions were also seen in cement and metals, driven by the ongoing contraction in the real estate sector.

Yet, the continuation of the trend is in no way a given. The country’s solar boom is running into grid constraints — largely artificial ones created by outdated grid management and policies favouring coal power plants, rather than real physical bottlenecks. Runaway growth in coal and oil consumption by China’s chemical industry has offset most of the emission reductions in the rest of the economy, turning a significant drop into a plateau.

Huge amounts of new coal- and gas-fired power capacity are still under construction, following the central government’s loosening of permitting requirements and promotion of new projects in response to electricity shortages in the early 2020s.

Electricity system reforms are progressing, and investments in electricity storage have accelerated, enabling the integration of significantly larger shares of solar and wind energy into the power system and rendering new fossil fuel power plants redundant.

In light of these developments, China’s policymakers face big choices. Due to rapid emissions growth during the COVID-19 pandemic, China is likely to miss its key carbon emissions target for the 2021–2025 period. When formulating the country’s next five-year plan, the leadership needs to determine whether to uphold their existing climate commitments for 2030, including reducing coal consumption and achieving a significantly larger reduction in the carbon intensity of the economy than they have delivered in the past five years, to make up for the resulting shortfall.

There is no more space in China’s energy market for continuing the clean energy boom and expanding coal mining and coal-fired power capacity, so they need to decide whether to slow down the growth of clean energy sharply or to begin scaling down the country’s coal industry faster than they had anticipated.

China’s original CO2 emission peaking timeline allowed for growth until just before 2030, as do the country’s recently announced climate commitments for 2035. Given that emissions have already levelled off, decision-makers must determine whether to allow an emission rebound in the next few years or to initiate the control of carbon intensity and absolute carbon emissions from next year.

In particular, will they allow the runaway growth of the fossil fuel-based chemical industry to continue, or do they emphasise electrification as the key way to reduce reliance on oil and gas imports?

What is clear is that China can cement its emission peak now and start making progress towards its 2030 emission targets and the 2060 carbon neutrality goal.

Continuing the clean energy boom is necessary if policymakers want to maintain the tailwind that the industry has provided to China’s economy in recent years. Clean energy sectors contributed more than 10% of China’s GDP in 2024, for the first time, based on our research. This research was recently cited by the country’s Vice Minister for Environment, Li Gao, indicating that decision-makers are aware of the economic stakes.

Lauri Myllyvirta is the co-founder and lead analyst of the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, as well as a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. He has more than a decade of experience as an energy analyst, tracking, advising, and producing research that influences and monitors energy, air quality, and emissions issues, and is one of the most widely cited commentators on China’s energy and CO2 trends.

CREA is an independent research organisation using scientific data, research and evidence to support the efforts of governments, companies and campaigning organisations worldwide in their efforts to move towards clean energy and clean air. CREA is headquartered in Finland, with 30 staff members across Asia, Europe, and North America.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Energy Tracker Asia.