Malaysian Banks and Their Slow Transition to Renewable Energy Finance

24 March 2021 – by Viktor Tachev

The UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (2015-2030) is to reduce global air pollution levels through climate action. Among the main enablers for achieving this aspiring goal are limiting fossil fuels like coal and shifting to renewable energy financing and investments in sustainable projects.

While many countries are fully committed to this mission, for years Malaysia was going in the opposite direction. The country is on a journey towards a greener future. However, local and commercial banks continuing to back coal-burning projects are hampering the efforts.

Malaysian Banks Remain Faithful to Fossil Fuels

The past few decades have seen Malaysia achieve massive development. According to the Environmental Kuznets Curve theory, a country’s progress usually goes hand-to-hand with a negative impact on its environment. For years, Malaysia has been ignoring the effects of its development on the environment and the people.

Fortunately, the local government has changed course. Malaysia has pledged to focus on renewable energy and cut carbon emissions intensity by 45% by 2030. The truth is it can’t do it without collaborating efforts from the corporate side, most importantly – the banks that should up their efforts in renewable energy investments.

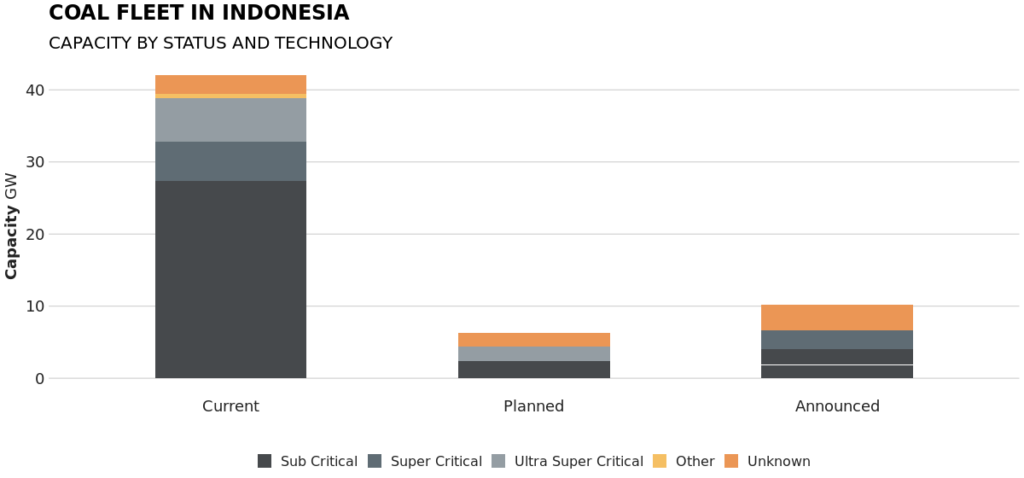

The problem is that some of the leading financial institutions in the country remain heavily invested in fossil fuels and coal-burning projects and aren’t currently financing renewable energy. During the last decade, Malaysia’s two largest banks have provided over USD $4.9b to corporate entities developing coal projects through loans and bonds. They are said to continue their lending policy by considering financing the controversial Jawa 9 and 10 project in Indonesia.

Maybank is Dead Wrong On Coal

One of the largest banks in Malaysia, Maybank continues to fund coals. Maybank is responsible for US $1.8 billion coal financing, despite the enormous risks coal causes the planet and our climate. In 2014, Maybank was involved in a syndication loan to Adaro Energy, one of Indonesia’s biggest coal producers. This is despite the fact that the bank, in its 2019 Sustainability Report had committed to not financing activities that could have significant adverse impact on the environment and surrounding communities. In a response to Greenpeace, Maybank had stated that they are currently developing a coal value chain framework that will determine the ideal energy mix for all the countries in the ASEAN region. With this framework, the bank intends to scope out related areas under their banking and advisory services that they will no longer partake in. This framework, according to Maybank, will be released publicly in 2021.

The Consequences of Siding With the Enemy of Renewable Energy Finance

As surprising as it may sound, there are still banks that finance coal projects. This is despite of it’s environmental effects and its implications on the global population, especially developing countries. Such consequences should have already sealed the fate of coal.

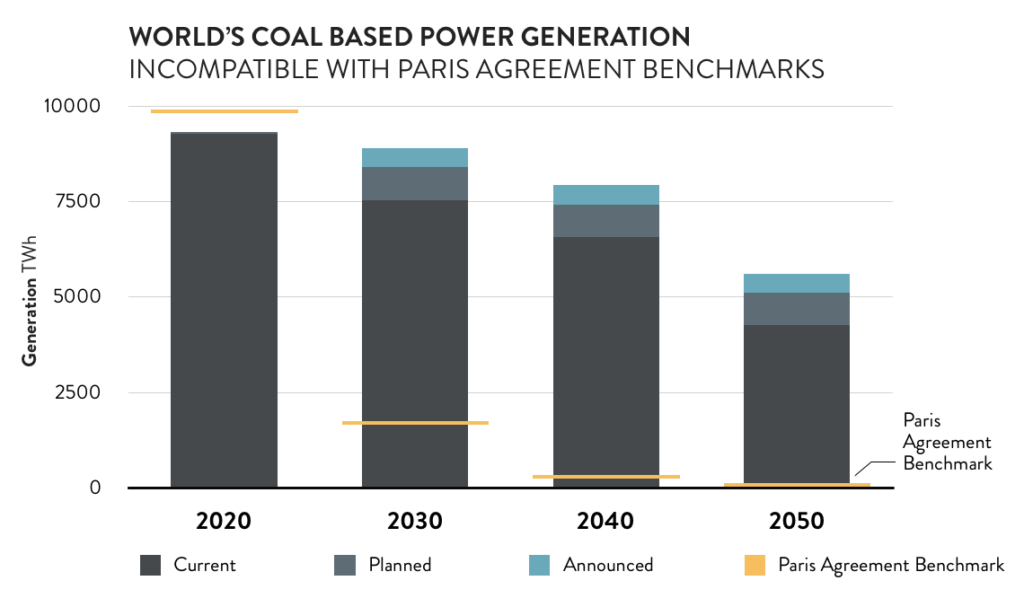

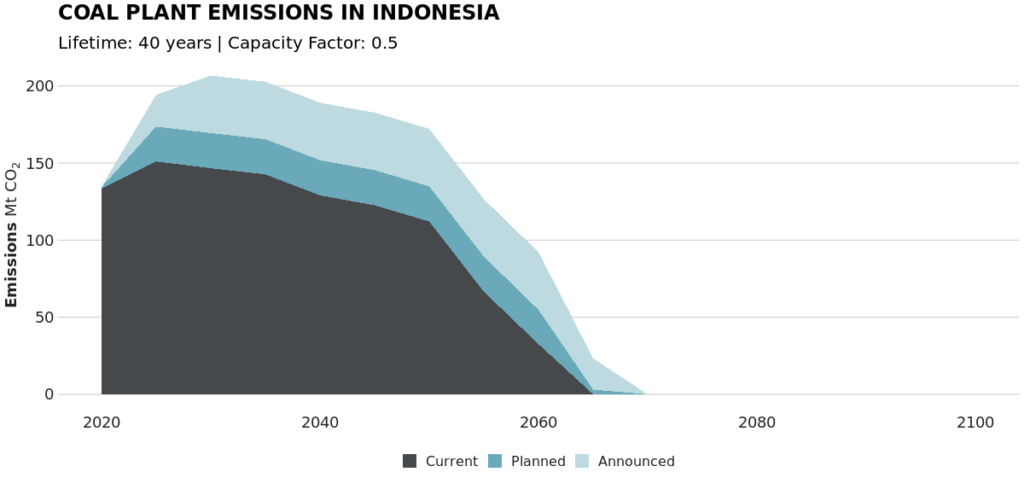

Experts suggest that to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees and meet the Paris Agreement commitments, countries should shut down all coal-fired power stations by 2040 at the latest. According to the International Energy Agency’s Executive Director, “We have no room to build anything that emits CO2 emissions.”

Renewable energy projects

Projects like Jawa 9 and 10 don’t hold only environmental risk. The Banten region, where the plants will be built, is currently populated with 52 coal power projects. Indonesia consistently makes the list of the top 10 countries with the highest air pollution levels. The health problems and struggles of the local population are well-known. According to estimations, Jawa 9 and 10 would cause over 4,700 premature deaths during its operating lifetime.

Many banks realize the issue and have already started to back off financing coal projects. As of October 2019, over 45 major international banks have adopted a policy restricting investments for such projects.

Those who continue funding coal-related projects risk losing credibility and the trust of the industry. Crédit Agricole, for example, ended its businesses with organizations backing coal operations, including mining, infrastructure, and power plant development.

Malaysian banks can’t risk jeopardizing their businesses and exposing themselves to the reputational and financial consequences associated with these types of projects. Continuous involvement in coal will only bring more risks as civil society organizations such as Market Forces, Greenpeace, and Trend Asia, just to name a few, put them under scrutiny.

Public unrest and regulatory scrutiny

Malaysia’s biggest coal financer faced increased scrutiny from civil society groups. As a result, it announced it would stop financing coal projects. However, pressure doesn’t come only from the public.

Malaysia’s Central Bank, Bank Negara, has urged local banks to take action. It targets to introduce a universal framework requiring financial institutions to report their exposures to climate risk. In 2019, the oversight authority joined forces with the Securities Commission to establish the Joint Committee on Climate Change (JC3) to drive and coordinate the financial industry’s collective response to climate risks. As a next step, the regulator issued the Climate Change and Principled based Taxonomy Discussion Paper to solicit feedback on the classification of assets associated with investment activities, based on their climate risk exposure.

Renewable Energy Finance as a Way for Banks to Avoid Reputational Damage and Financial Risks

Malaysia itself is already making a change. However, there is a need for an additional push from the financial sector. The local banking industry is a crucial force in implementing policies for change to clean energy in the Southeast Asia region’s energy sector. Banks’ willingness to leave coal financing behind will drive benefits on all fronts. First, it will protect themselves and their shareholders from the financial and reputational risks. It also contributes to the collective push towards a sustainable future.

Nor Shamsiah, Malaysia’s central bank governor, echoes the need for change. At the start of 2021, she warned of increased regulation. There will be clear and immediate prospects for differentiating financial institutions based on their efforts and support for climate goals.

To avoid exposure to or exacerbating the effect of the associated environmental, reputational, and financial risks, Malaysian banks should reconsider their involvement in the Jawa 9 and 10 in Indonesia and coal mining projects in Kalimantan. Failure to do so might also lead to legal consequences, considering that these projects are cited as potential contributors to Jakarta’s air pollution levels in a civil suit filed against the President and other officials.

Besides, banks should focus on releasing renewable energy finance policies in harmony with the Paris Agreement. More specifically, these measures should limit or, preferably, entirely rule out financing projects and organizations involved with the coal industry.

In a nutshell, banks should rethink their renewable energy investment approach and support for the dying coal industry. Instead, financial institutions should consider targetting projects within the inevitable and lucrative niche of renewable energy.

by Viktor Tachev

Viktor has years of experience in financial markets and energy finance, working as a marketing consultant and content creator for leading institutions, NGOs, and tech startups. He is a regular contributor to knowledge hubs and magazines, tackling the latest trends in sustainability and green energy.

Read more