COP29 Outcome Falls Short of An Ambitious Goal

25 November 2024 – by Walter James

The fault lines were painfully familiar – Global North versus Global South, industrialised versus developing nations and historic emitters versus vulnerable countries. The deeply disappointing outcome of the COP29 negotiations on climate finance is directly attributable to the same divide that has plagued UN climate summits for nearly three decades.

Objective of the COP29 Azerbaijan Climate Change Conference

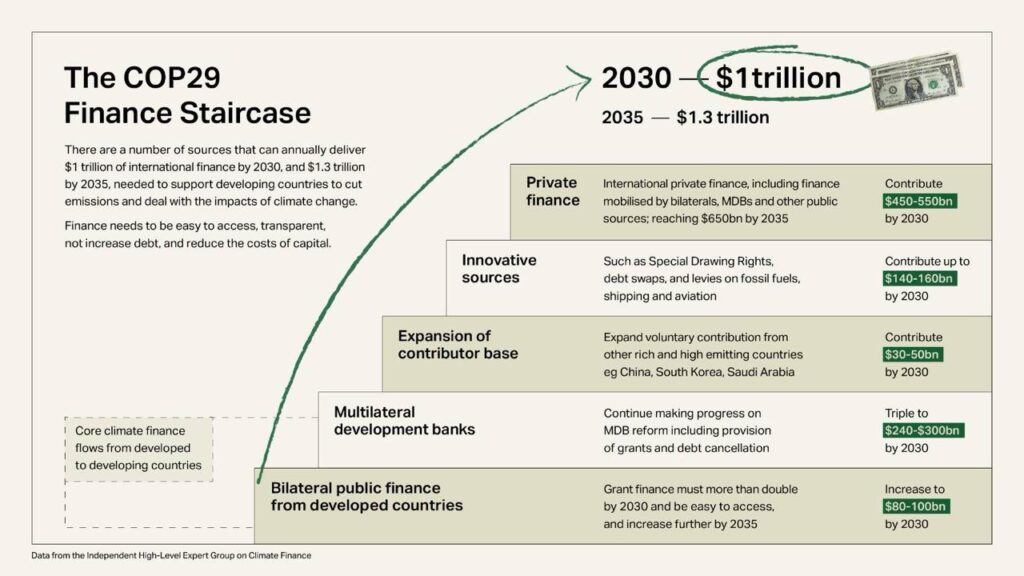

The overarching objective of the 2024 UN climate change conference, COP29 Azerbaijan, was to set a new goal for annual financial flows to the developing world. In 2009, countries agreed to deliver USD 100 billion by 2020. But, according to the UN-appointed Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG), the world needs USD 1 trillion per year by 2030 and USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 in external finance. The amount of 1.3 trillion became the reference number for the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) and a rallying cry for negotiators and civil society organizations in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Yet, after days of brutal international climate negotiations, the final text of the NCQG settled on USD 250 billion per year by 2035 — leaving a chasm between the USD 1.3 trillion goal and the amount countries are willing to pay.

New Collective Quantified Goal and the Climate Crisis

The IHLEG’s estimate of USD 1.3 trillion per year in international finance by 2035 is part of its larger projection of USD 7-8.1 trillion per year in total global investments required by 2035 to achieve the 2°C goal under the Paris Agreement.

An overwhelming sum at first sight, USD 1.3 trillion becomes a feasible figure when put into context.

“USD 1 trillion is about the amount of subsidies fossil fuels got in 2021-2022,” Amy Kong of Zero Carbon Analytics told Energy Tracker Asia in an interview. “It’s about 1% of global GDP. Developed countries managed to pull out around USD 10 trillion for COVID recovery.”

To address the defining crisis of our generation, USD 1.3 trillion in collective finance shouldn’t require a second thought.

The IHLEG was also clear on how this goal should be structured. Its core should come in the form of grants, as opposed to loans, in bilateral public finance from developed countries and multilateral development banks. Other sources, including international private finance, would play an important but secondary role.

The final text on the NCQG acknowledges the USD 1.3 trillion figure as the broad goal for “all actors” to work together meet by 2035. But as for the core finance goal for developed countries to mobilise, the text settled for USD 300 billion per year by 2035. This is to come from a “wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral” and would also include other sources.

The text also invites developing countries to make additional contributions to or supplement the new finance goal. Regarding the role of the major emerging economies — including China, India, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states — that were not originally classified as developed when UN climate summits began in the 1990s, the text “encourages” them to make contributions on a “voluntary basis”.

To reassure developing nations that progress to USD 1.3 trillion will happen, the text “decides to launch” the “Baku to Belém Roadmap to 1.3T,” which aims to scale up climate finance to developing countries over the next year. How the roadmap plans to do this is unclear.

Reactions to the Final Agreement of COP29 Baku

Reactions to the climate finance deal during the summit’s closing plenary varied in tone but were unanimous in their disappointment.

Ani Dasgupta, president and CEO of the World Resources Institute, was among the more measured. He said that while the agreement “is an important downpayment toward a safer, more equitable future,” it still “does not meet the scale of what developing countries need to pursue a low-carbon economy and protect their citizens from mounting droughts, floods and wildfires”.

The Climate Group’s Champa Patel said, “With this paltry USD 300 billion a year commitment, COP29 has slammed the door in the face of developing countries.” Patel pointed out that the agreement leaves the structure of climate finance in the dark. “The target has no clear percentage for how much of this funding should be grants or concessions rather than loans.”

Tasneem Essop, executive director of Climate Action Network, said in a written statement: “This has been the most horrendous climate negotiations in years due to the bad faith of developed countries. This was meant to be the finance COP, but the Global North turned up with a plan to betray the Global South.”

Developing countries’ envoys were also scathing. India’s negotiator, Chandni Raina, said the goal was a “paltry sum” and that the COP Presidency did not allow opposing voices to state their case. She said, “Gavelling and trying to ignore parties from speaking does not behove the UNFCCC’s system and we would want you to hear us and also hear our objections to this adoption.”

Consequences

The COP29 2024 climate finance agreement has far-reaching consequences for climate action in least developed countries and the global landscape of climate and energy politics.

Stunting Climate Actions in Developing Countries

Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required to submit their updated nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that outline their Paris-aligned climate actions by February 2025. For developing countries, their climate action roadmap critically hinges on the availability of climate finance. The lacklustre commitment by wealthy nations to provide finance will very likely impede ambitious climate action by much of the rest of the world.

This scarcity of accessible capital for climate mitigation and adaptation will continue to exacerbate what UN Executive Secretary Simon Stiell characterised as a “two-speed global transition,” whereby clean energy investments are unevenly distributed across the world.

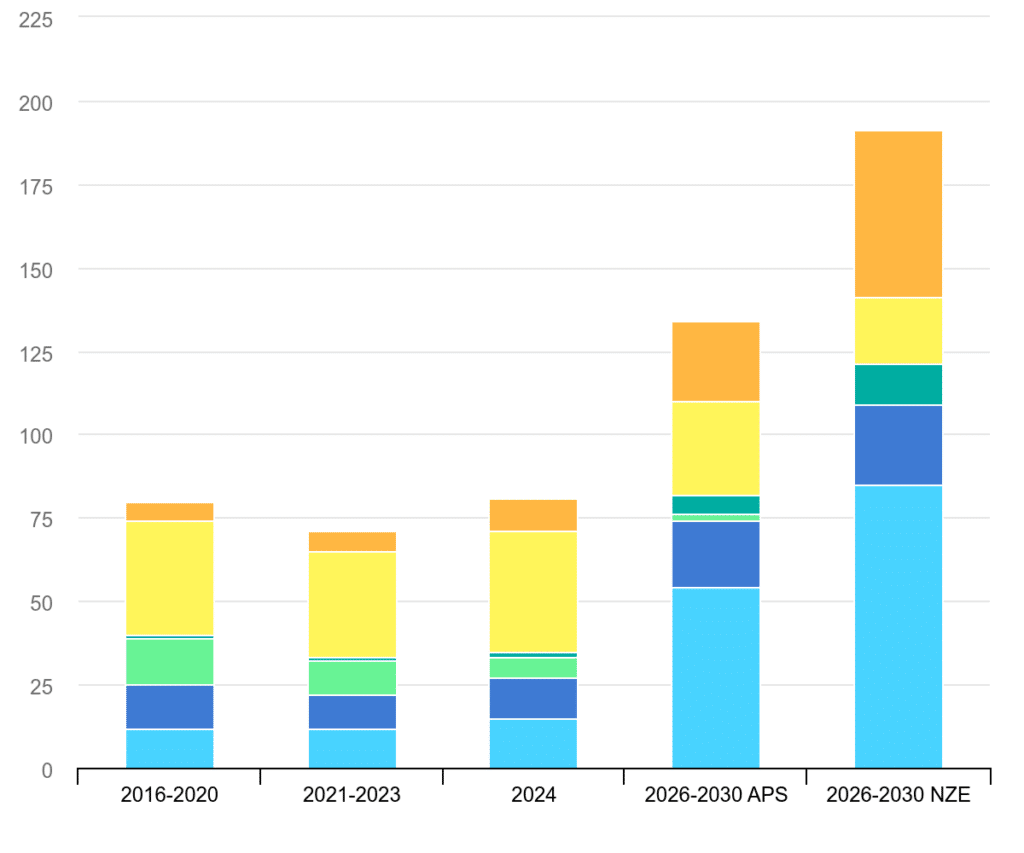

Large parts of Asia will be hard-pressed to take ambitious climate action. According to the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions scenario, Southeast Asia will need USD 190 billion in annual investments from 2026-2030 for countries in the region to meet their carbon neutrality targets. In contrast, the region’s annual average energy investments over the last three years was USD 72 billion.

Accessible and equitable climate finance would also enhance the region’s resilience to geopolitical shocks. “Many Southeast Asian and South Asian countries rely on fossil fuel imports,” Zero Carbon Analytics’ Amy Kong told Energy Tracker Asia during the Baku climate talks. “So, being able to build up a renewable base will help them lower import costs significantly. Having a strong NCQG is very important to help them meet those goals.”

Shifting Center of Gravity in Global Climate Governance

Developed countries’ resistance to committing to an ambitious climate finance goal and attempts by some petrostates to thwart the COP process are leading to a shift in the landscape of global climate governance. The anticipated US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement under Donald Trump’s second presidency — a repeat of 2017 — greatly contributes to this shift.

Jihyeon Ha of Solutions for Our Climate, a South Korea-based think tank, told Energy Tracker Asia in a written statement: “As the tides are turning with the recent results of the US elections, changes in global climate leadership are being shined on to Asia, and particularly China.” China, now the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, is also one of the largest contributors of climate finance globally.

Zhe Yao, Greenpeace East Asia’s global policy advisor, also said in a written statement that “China’s decision matters. COP29 has shown a clear need for climate leadership, but the trillion-dollar question is how determined China is to turn its strengths on clean technology into leadership?”

The changing playing field away from rich countries and toward China and other developing countries was plainly evident at COP29. In response to the penultimate draft proposal, 116 civil society organisations signed a letter addressed to the developed countries, making it clear that they are “deeply outraged in your destructive role in creating an absolutely unacceptable NCQG draft negotiating text on this final day of COP29”.

Another letter, signed by 335 organisations, expressed their support for the G77+China, a coalition of over 130 developing countries. It reads, “We urge you to stand up for the people of the Global South,” adding, “If nothing sufficiently strong is forthcoming at this COP we urge you to walk away from the table to fight another day, and we will fight the same fight.”

More Work on the Horizon for Climate Finance

Touted as the “Finance COP,” the 29th UN climate summit delivered a new climate finance goal that, by all accounts, fell far short of expectations. The goal of USD 300 billion per year by 2035 is merely a downpayment for further climate finance contributions by wealthy nations, larger emerging economies and multilateral institutions.

Much of that work will need to be done between now and COP30 in Brazil and beyond. In the meantime, the focus of global climate leadership appears to be moving away from the developed nations to China.

by Walter James

Walter James is the principal consultant at Power Japan Consulting, which offers research, writing, and consulting services related to Japan's climate and energy policies. He also writes about these topics on his Power Japan Substack. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Temple University and is a former research fellow at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.

Read more