Japan’s Industrial Policy for Floating Offshore Wind

Source: Flickr

20 April 2025 – by Walter James

Japan wants to build a huge, expensive high-tech industry that will power a major economy as fast as possible and as safely as possible — and that’s what it’s trying to do with offshore wind.

Of all the renewable energy options on the table, offshore wind holds the greatest promise for Japan. The nation’s geographic isolation and mountainous terrain limit onshore renewables. But its oceans are brimming with potential for Japan’s climate targets, energy security and international competitiveness. Turning that potential into electricity requires a mass deployment of offshore wind turbines — in particular, floating offshore wind turbines.

Japan’s Wind Energy Potential

Surrounded by windy seas, Japan boasts enormous offshore wind potential. According to one estimate, the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) could support up to 552 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind capacity. That’s more than five times Japan’s current total electricity generation capacity.

Yet in 2023, Japan had just 187.7 megawatts (MW) of installed offshore and semi-offshore wind capacity — 0.03% of its technical potential. This was also a fraction of what countries like China, the UK and Taiwan have achieved, according to the Global Wind Energy Council.

The Japan Wind Power Association has set an ambitious target: 140 GW by 2050, of which 60 GW would come from floating offshore turbines. Achieving this target would represent a colossal leap from the status quo.

The government also recognises offshore wind’s promise, positioning it as a game changer in its 7th Strategic Energy Plan published in February 2025. It’s also aware of offshore wind’s co-benefits, asoffshore projects are massive in scale and involve a host of industries throughout their value chain. This could kick-start a positive chain reaction of job creation, technological innovation, investments and international competitiveness.

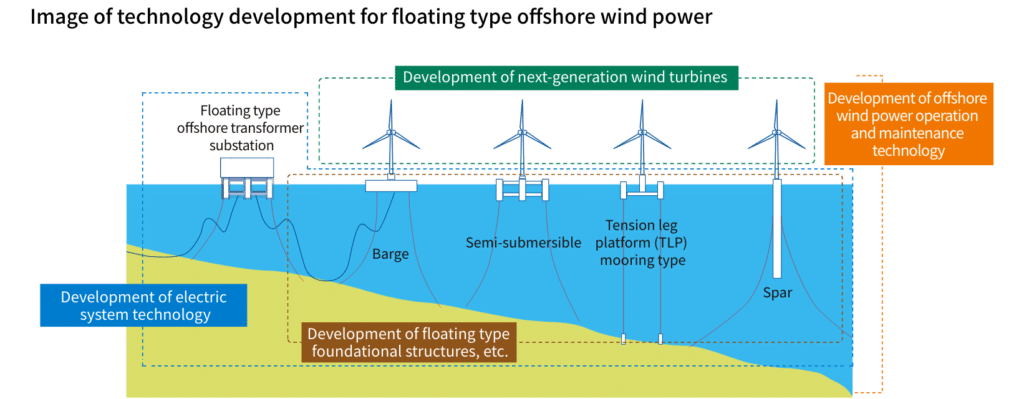

Floating Offshore Wind Industrial Policy in Japan

The government and private sector share the ambition to nurture the nascent floating offshore wind industry. To this end, they are taking a number of steps.

Legislative Reforms and Subsidies

In February 2023, a group of lawmakers in the ruling Liberal Democratic Party formed a parliamentary alliance aimed at accelerating the rollout of “next-generation” domestic renewable technologies, especially offshore wind. This move has political tailwinds. In his January 2023 policy speech, then-Prime Minister Fumio Kishida underlined the need to secure “diverse energy sources” for a stable supply. Offshore wind, especially the floating variety, is a clear candidate.

The government bureaucracy has also been undertaking multifaceted legislative and regulatory reforms to promote floating offshore wind. The 2020 “Vision for Offshore Wind Power Industry” set a national target of 10 GW by 2030 and 30-45 GW by 2040. But it did not specify targets for floating offshore wind capacity. In March 2025, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) and Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) began working on a second edition of the vision, which will introduce floating-specific targets for the first time.

In January 2024, the government approved a major legal reform to expand offshore wind development beyond territorial waters and into Japan’s EEZ. The EEZ is where the vast majority of Japan’s offshore wind potential lies, and deep-sea floating projects require access to EEZ zones, where prefectural authority does not apply. The reform introduces a more structured, two-stage approval process, based in part on the UK model. Developers would first receive leasing rights, then be required to negotiate with stakeholders such as fisheries before receiving final construction permits.

In parallel, government-backed institutions are providing subsidies for technological and supply chain development. The New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO), for example, is investing heavily in cost reductions, aiming to bring the price of electricity generated by fixed-bottom wind power to JPY 8-9 per kWh by 2030 and to commercialise floating offshore wind at globally competitive costs. The government also awarded JPY 12.6 billion in subsidies to five firms through its GX Supply Chain Construction Support Project in January 2025.

Private Sector Initiatives

For their part, Japan’s energy and engineering industries are taking their own steps to develop a domestic supply chain necessary for a vibrant floating offshore wind industry. In March 2024, major utilities including Tohoku Electric and Kansai Electric helped launch the Floating Offshore Wind Technology Research Association (FLOWRA), a 21-member consortium focused on large-scale floating wind commercialisation. NEDO has backed the initiative with JPY 4 billion in funding.

In a similar vein, specialist companies in the construction, steel engineering, shipbuilding, and lifting machinery sectors founded the Floating Offshore Wind Construction System Technology Research Association (FLOWCON) as a partner entity to FLOWRA, with the mission to build cost-effective floating structures at scale. To develop the highly skilled workforce needed for manufacturing, building and maintaining floating offshore wind turbines, a public-private initiative called Education Council for Offshore Wind (ECOWIND) was established in June 2024, bringing together power generation and construction companies and education and research institutions.

Offshore Wind Development in Japan – Prevailing Challenges

Despite these reforms and initiatives, a number of challenges still stand in the way of Japan’s nascent floating offshore wind industry.

First, there are significant macroeconomic hurdles for both fixed and floating offshore wind. Since 2021, rising global material costs have pushed up supply chain expenses beyond what Japan’s current bidding system can absorb. As the Renewable Energy Institute (REI) notes, “zero-premium” bids are unsustainable when inflation and currency volatility remain high. A perfect illustration of the rising costs came in February 2025 when Mitsubishi Corporation announced a massive JPY 522 billion impairment loss on three offshore wind farms for which it won development rights in the first offshore wind auction in 2021. Mitsubishi is now re-evaluating the viability of the projects from the ground up, even considering a full-scale retreat.

Japan’s slow permitting process also acts as an administrative bottleneck. Environmental assessments alone take several years on average and involve multiple government agencies. These inefficiencies prompted foreign firms to call for faster, larger auctions to reduce risk and improve business certainty.

There are also concerns that Japan’s infrastructure is not equipped for floating offshore wind. While Japan has over 1,000 ports, only a handful can store and assemble offshore turbine blades and towers, and handle large crane vessels or maintenance ships. Upgrading the power grid to handle the large volumes of electricity generated by offshore wind is another challenge. In areas with favourable wind conditions, such as northern Japan, there is limited capacity in the existing transmission grid, and constructing new lines or reinforcing the system requires significant time and expense.

A Long Road Ahead

Japan’s potential to lead in floating offshore wind is immense. While it is still years away from maturity, deploying floating wind turbines in the country’s EEZ will fundamentally transform its energy security, domestic economy, international competitiveness and approach to climate change. The government and private sector are united in formulating new legislation, initiating public-private coordination and mobilising early-stage investments. But cost inflation, grid bottlenecks and infrastructure shortfalls threaten to slow progress. How the industry and policymakers navigate global headwinds, market dynamics and domestic constraints will determine whether floating offshore wind becomes a cornerstone of Japan’s energy future.

by Walter James

Walter James is the principal consultant at Power Japan Consulting, which offers research, writing, and consulting services related to Japan's climate and energy policies. He also writes about these topics on his Power Japan Substack. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Temple University and is a former research fellow at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.

Read more