Philippines Weighs High-Stakes Carbon Pricing and Common Market Pitfalls [Op-Ed]

Photo: Shutterstock / La Terase

10 February 2026 – by The Climate Reality Project Philippines

Ranked the world’s most vulnerable nation, the Philippines is forging ahead with high-stakes domestic regulatory carbon pricing to reduce global emissions input. A policy report warns that, without social and environmental guardrails, the proposed system could legitimise pollution and fail to deliver meaningful emissions cuts.

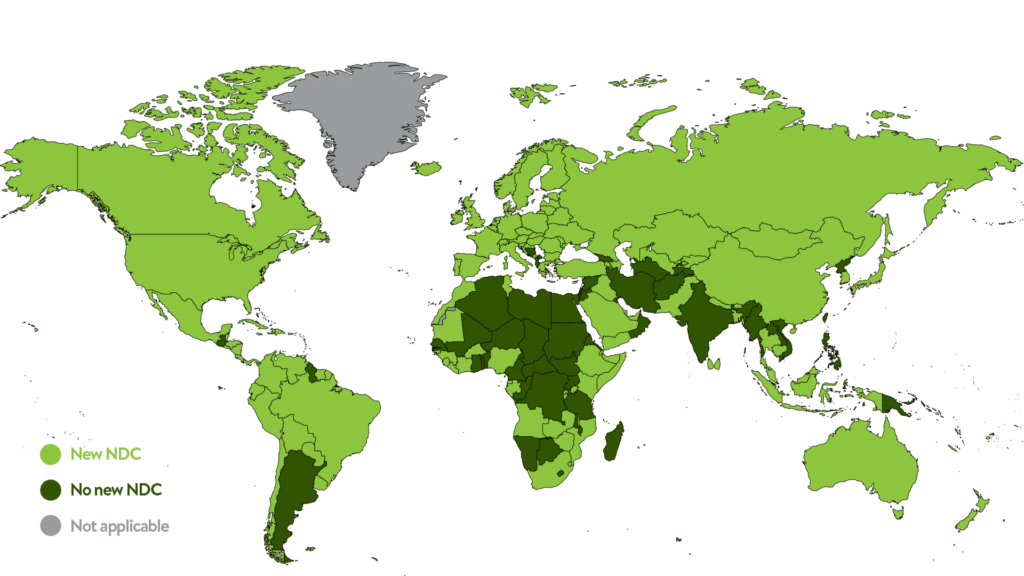

As international climate negotiations stall, with about 60% of countries failing to submit their updated national climate targets within the extended deadline, the Philippines is developing its own rules for carbon pricing as a climate mitigation strategy and turning inward to address the climate crisis by seeking domestic solutions to drive down emissions and finance climate resilience and survival.

It is advancing pioneering legislation to establish an emissions trading system (ETS) through the Low Carbon Economy Investment Bill. Under this bill is the proposed cap-and-invest framework intended to raise revenue from auctioned emissions allowances and to reinvest the proceeds in renewable energy transition and other climate mitigation programmes.

Pledged under the Paris Agreement, the Philippines aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 75% by 2030 relative to business-as-usual levels. Ambitious, yet the ultimatum is that over 72% of this target is conditional on receiving international finance and support. An ETS is seen as a market mechanism to unlock private capital and reduce reliance on unpredictable foreign aid. A policy analysis by The Climate Reality Project Philippines examines the current realities of the country’s social and environmental preparedness for carbon pricing, such as an ETS.

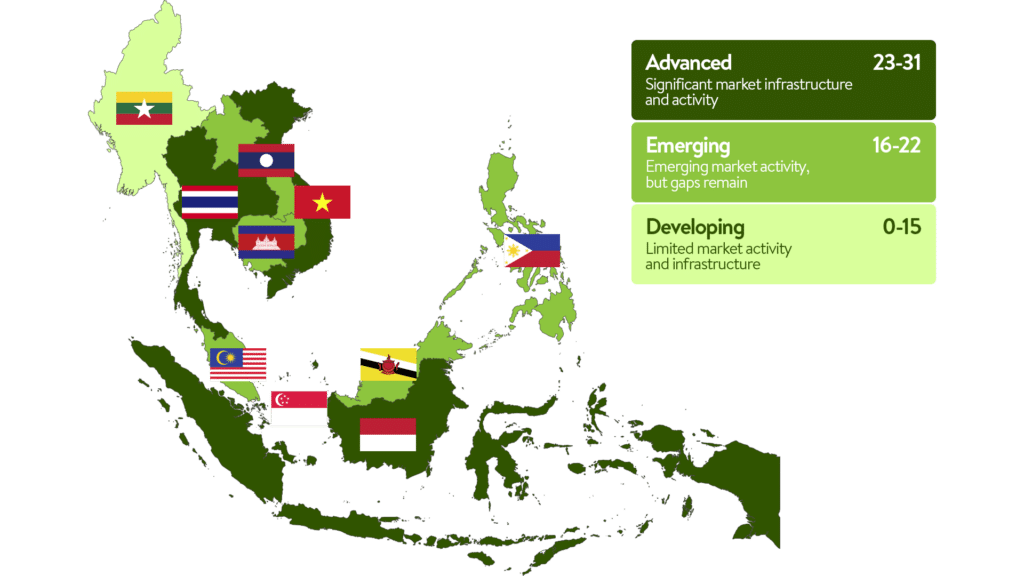

Keeping Pace in a Racing Asian Market

The Philippines is definitely not acting in isolation, given the race, it must sprint alongside its neighbouring Southeast Asian and Asian countries. Across ASEAN, carbon credits are rapidly taking over the markets as countries seek to lower their emissions. Indonesia has a hybrid carbon pricing model, combining taxation and mandatory emissions trading for the power sector. Vietnam has finally put in place a legal and regulatory framework for its domestic carbon market, allowing regulated entities trade carbon credits and greenhouse gas emissions quotas. Singapore is positioning itself as a global hub for carbon services, pioneering the development of “transition credits” to finance the early retirement of coal-fired power plants (CFFPs). In the Philippines, where coal still dominates the country’s energy mix, these market mechanisms offer pathways to accelerate the clean energy transition. ASEAN member states follow through on this momentum, including Brunei, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Thailand.

The Philippines has bilateral agreements with Japan for its first attempt to use the Article 6.2 mechanism for emission reductions from rice paddies, and another pilot project with Singapore to generate high-quality transition credits from the early retirement of CFFPs under the Coal-to-Clean Credit Initiative and the Energy Transition Mechanism.

Asia accounted for 50% of global GHG emissions, of which a third are from fossil fuel and cement producers. That alone, if these plants operate as planned, they will exhaust two-thirds of the remaining carbon budget to keep global temperature rise from increasing to within 1.5°C.

Deep Dive Into the Key Report Findings

Beneath the surface of the country’s landmark legislative proposal lie counterproductive aspects of its salient features. Providing a ground-truth assessment of the Low Carbon Economy Investment Bill, the study interviewed Filipino scientists, academics, and civil society organisations, with insights found gaps in the policy’s objectives.

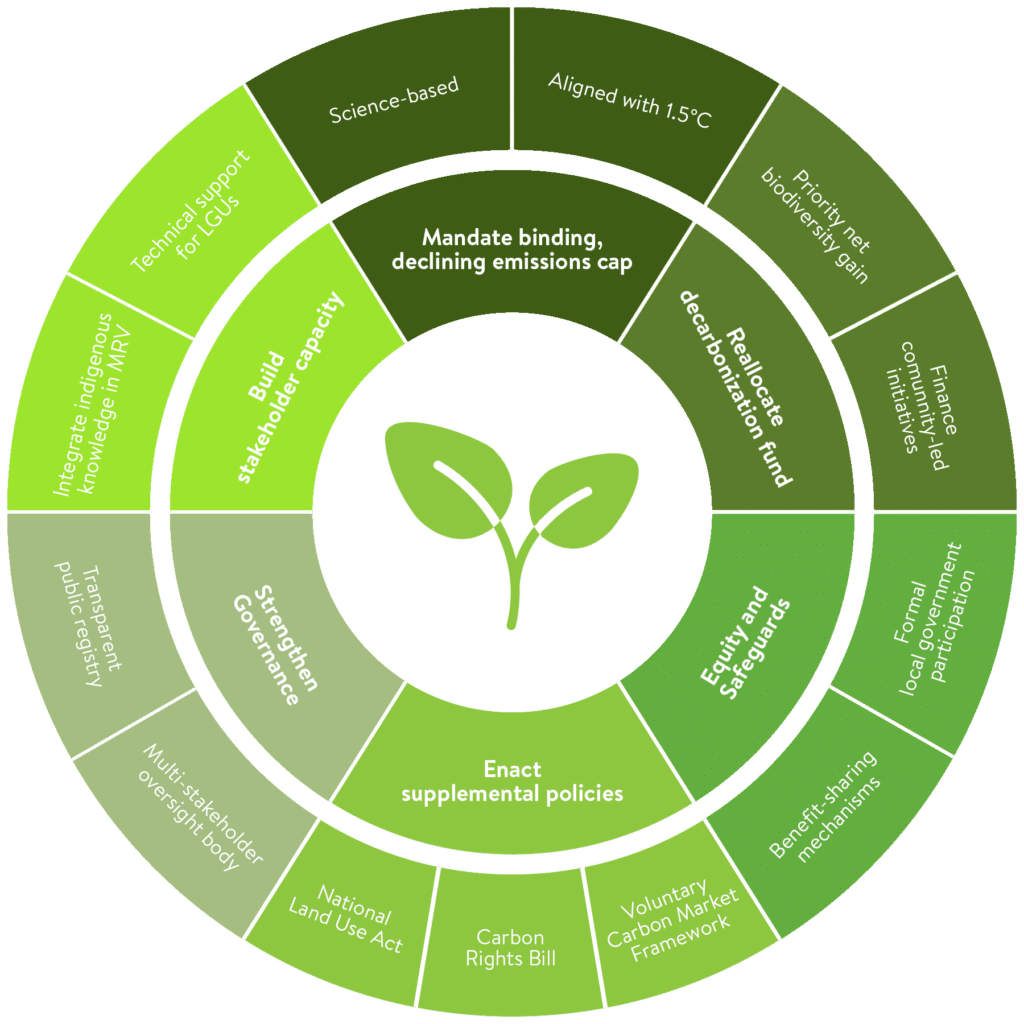

- The core weakness of the legislature as a whole is its inability to set the cap. An effective ETS is an absolute, declining cap on total emissions that provides certainty of how much emissions are being reduced. According to the bill, the cap and sectoral emissions allowances will be based on the consolidated decarbonisation plans from the regulated enterprises. In this corporate-driven approach, there is no guarantee that the emissions trajectory will align with the national emissions reduction targets in the Nationally Determined Contribution or with the imperative to limit warming to 1.5 °C. An absolute cap must decline predictably over time.

- The bill will establish a decarbonisation fund that undermines the polluter-pays principle. As a compliance mechanism for companies exceeding their mandated allowances, they must contribute to the fund, and these funds can be reinvested into projects outside a company’s value chain. This creates a dangerous loophole that allows firms to comply financially without making operational changes to reduce emissions at their source.

- The bill is silent on social justice and environmental safeguards. It lacks enforceable provisions to protect Indigenous Peoples’ rights and offers no legal framework for the equitable sharing of proceeds with local communities. Ecologically, the focus on carbon tonnage could incentivise the establishment of damaging monoculture plantations for offsets, sacrificing biodiversity and resilience for quick credits. With these vital safeguards in mind, the bill must protect human rights and ecological integrity, and mitigate risks of exacerbating existing inequalities and conflict.

- The proposed governance structure is a recipe for bureaucratic inefficiency, as the bill has no clear delineation between the mandated government agencies, which is critical to its enforcement. More specifically, it completely disempowers subnational governments, failing to grant them the authority to decide on or monitor projects within their jurisdictions. Stripping frontline governance centralises decision-making away from affected communities and leads to misalignment with local climate and land-use plans.

- Lastly, the proposed carbon pricing system cannot function effectively without supplemental legislation such as the Carbon Rights Bill, which is urgently needed to define tradable and property rights of carbon to prevent exploitation and conflict. Equally important is the National Land Use Act, which would provide for planning to prevent lands designated for nature-based carbon projects from later being converted for other uses. Furthermore, the full implementation of the Philippine Ecosystem and Natural Capital Accounting System Act (PENCAS) is required to supply the localised data for accurate carbon accounting.

In the end, the report does not dismiss the potential of either the proposed market mechanism or the legislative text. It is the only appropriate choice to deliver the maximum benefits of carbon pricing instruments, advancing the goal of a low-carbon economy. The success of a carbon market cannot be measured in pesos per tonne alone, but in the lives and livelihoods it protects, the forests and reefs it restores, and the justice it delivers to those who have contributed the least to the climate crisis. The report offers the other side of the system: a fair, just and genuine system that harnesses investment to heal our relationship with the environment. Despite the urgent race to decarbonise, countries must not leave their people and environment behind.

This analysis is based on the policy report Carbon for Sale: Weighing the Social and Environmental Costs and Opportunities of Establishing an Emissions Trading System in the Philippines (2025). For more details about the Climate Reality Philippines study, visit their resources page.

The Climate Reality Project Philippines is a country chapter of the global nonprofit founded by former US Vice President and Nobel Laureate Al Gore. Home to almost 1,900 trained Climate Reality Leaders, Climate Reality Philippines works at the intersection of science, advocacy, and policy to catalyse urgent climate action.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Energy Tracker Asia.