UBS Quits the Net-Zero Banking Alliance: The Consequences

20 October 2025 – by Viktor Tachev

The Swiss bank UBS has been among the founding members of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), an initiative driven by the world’s leading banking institutions, to advance global decarbonisation goals through their financing activities and achieve net zero by 2050. Over the years, the number of NZBA members increased from 43 banks upon launch to 144 in 2024. However, in 2025, the coalition experienced a mass exodus of members, ultimately derailing its future. Many of the biggest names in the industry quit. Yet, through the lenses of Southeast Asia’s energy transition, the exit of the Swiss UBS can prove the most important action due to the bank’s significant portfolio exposure to fossil fuel developers operating across the region.

Still, with or without the NZBA, it is up to every bank to ensure they are acting in good faith and are channelling their financial support towards investments in line with the Paris Agreement goal — not projects that continue to exacerbate the climate crisis.

UBS Quits the Net-Zero Banking Alliance

On Aug. 7, UBS announced that it had withdrawn from the UN-backed Net-Zero Banking Alliance, after its “annual assessment of sustainability- and climate-related memberships,” noting that although the alliance had provided valuable frameworks for initial target-setting, the institution had advanced its own capabilities. With the move, UBS becomes the first major European bank outside of the UK to exit the coalition.

UBS joined the initiative in 2021 as one of the founding members. In its Climate Report 2021, the bank revealed that it was working with other members “to develop necessary methodologies, frameworks and guidelines to reach net-zero emissions latest by 2050”. It also committed to “publishing ambitious intermediate targets for priority sectors” and to continue “to engage with power generation and extraction companies [among others] on their climate transition plans, and raise our voice with stragglers”.

The withdrawal follows UBS’ decision from earlier this year to push back its net-zero target for operations by 10 years, from 2025 to 2035. The bank is also no longer committed to the previous target of aligning 20% of its assets under management with net zero by 2030. UBS attributed the moves to the recent acquisition of another Swiss giant, Credit Suisse.

UBS’ announcement is the latest in a series of big exits that have posed a significant blow to the NZBA. Earlier this year, the UK-based HSBC and Barclays, as well as Canada’s leading banks, all withdrew from the alliance. The moves followed the mass exodus of US majors, including JP Morgan, Citi, Bank of America, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo, which all left the coalition between the end of 2024 and January 2025. Japanese and Australian banking institutions have also recently quit the NZBA. This series of events even prompted the alliance to initiate a member vote to decide on a proposed transition from a membership-based coalition to establishing its guidance as a new framework initiative. Following the vote, at the beginning of this month, a spokesperson announced that the NZBA would no longer be a member-based alliance and would cease operations immediately.

However, banks leaving climate alliances are not just symbolic events but often a reflection of deeper shifts in how financial institutions perceive collective commitments, regulatory risk, geopolitics and their sustainability strategies. For example, the mass exodus from the NZBA began soon after Trump won the US election and launched his organised campaign against climate action, including pulling out of the Paris Agreement, reverting key environmental laws and prioritising coal and gas buildup at the expense of renewables.

“We are witnessing a major anti-ESG backlash originating in the United States and increasingly influencing Europe,” explained Johanna Frühwald, finance campaigner at Urgewald, in an interview for Energy Tracker Asia.

NZBA Doomed From the Start?

It wasn’t UBS’ decision that brought the initiative to a halt. In fact, it was starting to show cracks a lot earlier, with experts from BankTrack largely questioning its effectiveness and noting that the coalition had never been up to the task. European Central Bank research argues that such voluntary private-sector initiatives may have a relatively limited impact on decarbonisation.

“Even before the Net-Zero Banking Alliance began to fall apart, it had already failed to deliver on its commitments. What we need is climate action, not climate rhetoric. Many of the first members to withdraw were, in any case, never truly there to drive change, but rather to create the illusion of progress,” Frühwald notes.

The coalition has long been criticised for lacking any obligation to tackle fossil fuel financing, the main driver of the climate crisis. In total, financial institutions have provided over USD 385 billion to the coal industry since 2021, when the NZBA launched. In 2024 alone, the world’s leading banks granted fossil fuel firms USD 869 billion in financing.

Furthermore, in April this year, the NZBA voted to loosen the requirement for members to align their portfolios with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the global temperature rise to a maximum of 1.5°C by the end of the century. Instead, the new guidance introduced vague language on the goals of members, including to limit global warming to “well below 2ºC, striving for 1.5ºC”.

“The NZBA experience clearly shows that voluntary alliances are not sufficient to shift financial flows from fossil fuels to renewables. Ultimately, fossil finance must be effectively regulated — not only for climate reasons, but also to safeguard the stability of the financial system. Central banks, financial regulators and supervisory authorities must finally take a more active role,” Frühwald states.

UBS Faces Criticism Over Gap Between Sustainability Rhetoric and Contradictory Fossil Fuel Practices

In a press release following the exit from the NZBA, UBS reaffirmed its ambition to be “a leader in sustainability”, promising to continue progressing its strategy to “Protect, Grow and Attract”. Importantly, the bank claims it considers climate change risks and opportunities for the benefit of its clients, investors, and all of its stakeholders.

Despite this, UBS hasn’t yet committed to a coal phaseout and has scrapped the commitment of its acquired Credit Suisse bank to reduce coal exposure to 5% by 2030.

As per its 2024 report, by 2030, UBS aims to reduce “absolute financed emissions associated with UBS in-scope lending from 2021 levels for fossil fuels by 70%.” Among the key achievements for 2024, the bank identifies exceeding its 2030 fossil fuel lending decarbonisation target, with estimated financed emissions having decreased by 80% in 2023 compared to the 2021 baseline.

While Reclaim Finance considers UBS’ target one of the most ambitious among all NZBA members, the experts note that it remains highly selective and somewhat misleading. The reason is that UBS’ fossil fuel expansion projects aren’t financed through loans, but rather through general corporate finance, such as bond issuances, which aren’t covered by the institution’s emissions reduction target.

The bank’s report also states that with the remaining concentrated portfolio, it would not expect “the same level of emission reductions over the next few years,” due to the reliance on fossil fuels “for energy security and because it is the most affordable source of energy in many countries”.

However, this isn’t the case for many Southeast Asian countries. For example, solar power is already cheaper than natural gas in the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand. Furthermore, fossil fuels’ import dependence, paired with the price volatility on global markets, has left many Asian countries starving for power or made them pay above-market prices for deliveries in recent years, ultimately undermining their energy security. The unaffordably high LNG prices have also led to the volatile demand being far from projected, reducing the appetite for gas in key Asian markets and exacerbating the stranded asset risk facing investors.

Asked about the discrepancies between UBS’ public communication and the reality painted by its financing activities and the findings in BankTrack’s report, Frühwald, says that the bank has a strong interest in presenting itself positively to the public and creating the impression that it is pursuing a sustainable path and taking ESG concerns seriously.

“While UBS has indeed made some progress on the banking side, having reduced its financing of fossil fuel companies in recent years, it still ranks among the world’s largest banks supporting the fossil fuel industry,” the expert explained.

Experts Link UBS’ Financing to Leading Fossil Fuel Developers in Southeast Asia and Globally

According to BankTrack, the Swiss banking giant is underwriting some of the world’s biggest fossil fuel developers, including offering billions of dollars in finance to carbon majors such as BP, Gazprom, Petrobras, Saudi Aramco, KEPCO, Shell and Woodside Energy, among others. Reclaim Finance has also identified links between UBS and ExxonMobil, one of the biggest corporate climate polluters in history, which also plans to continue increasing its oil production output in the near future. Australian campaign group Market Forces revealed that UBS’ bond offerings are also supporting Woodside Energy, Australia’s largest gas producer.

Furthermore, Greenpeace notes that UBS doesn’t limit its support for fossil fuel expansion to bond issuances, but also expands it through its asset management business.

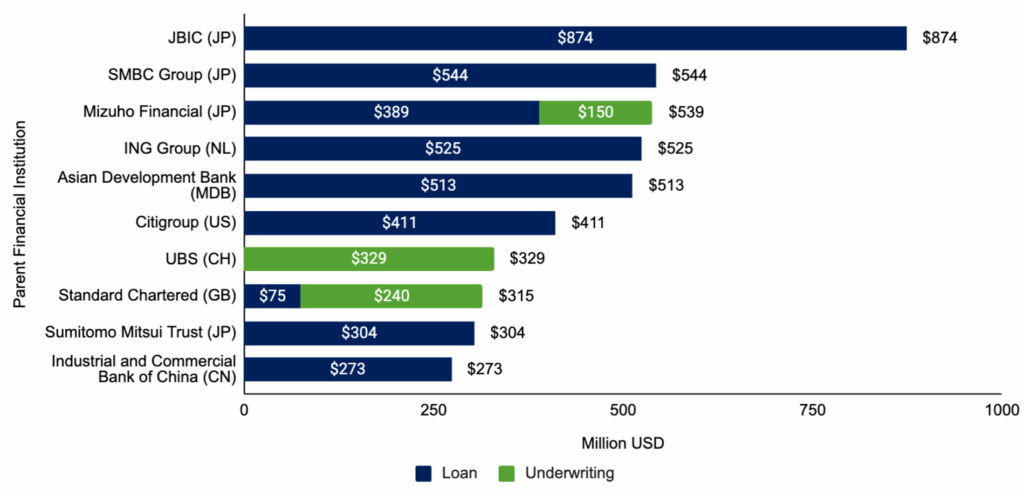

According to the Southeast Asia Divestment Scorecard, UBS is among the top 10 international financing institutions with the biggest downstream gas project financing, with the majority of financial support delivered through underwriting.

UBS’ ties to fossil fuel financing in Southeast Asia can be traced to leading developers, including San Miguel Corporation, JBIC and Gulf Development.

Data collected by the Japan Center for a Sustainable Environment and Society (JACSES) shows that UBS holds USD 26.7 million worth of JBIC bonds as of August 2025. Friends of the Earth Japan claims that JBIC had previously enabled projects associated with corruption, human rights violations and environmental damage.

Experts also find that UBS remains the second largest shareholder of Gulf Development, Thailand’s largest private power producer and a major developer of natural gas-fired power projects. The Clooney Foundation for Justice alleges that Gulf Development uses legal intimidation to undermine democratic processes and silence dissent. Others have expressed concerns about the company’s track record in potential violations of fundamental human rights. Since 2020, Gulf has reportedly pursued civil and criminal defamation lawsuits, seeking damages totalling more than USD 18.47 million against multiple individuals, including activists, political parties and academics, who have criticised the company.

According to researchers, UBS also holds USD 16.3 million worth of bonds in the power plant division San Miguel Global Power. This puts UBS in second place in Europe and sixth worldwide among the top institutional investors in San Miguel’s power plant division.

Public Backlash Against UBS Grows

UBS’ NZBA exit came amid growing calls from Asia for the bank to cease its financing of fossil fuels. Earlier this year, civil society organisations, led by Southeast Asian and Japanese groups, sent an open letter to UBS, asking it to drop its support for JBIC. The letter claimed that through its continued financing, UBS was complicit in the devastation happening across countries and communities.

A group of frontliners also spoke before UBS shareholders, calling for an end to its ties with San Miguel Corporation (SMC) and other prominent leaders in gas expansion across Southeast Asia. Over the years, SMC has been associated with two major oil spills and scandals revolving its fossil fuel development plans in the Verde Island Passage (VIP), a protected marine area near the Philippines, referred to as “the Amazon of the oceans” and home to nearly 60% of all known coastal fish species in the region. According to reports, the company, which is the largest gas expansionist in Southeast Asia, aims to turn the VIP into a major gas hub, which would threaten the livelihoods of the more than 2 million people who rely on the area.

“Exceeding the 1.5°C global warming limit threatens the survival of the Filipino people and other climate-vulnerable communities across the world. Instead of committing to the country’s climate and energy ambitions, companies like San Miguel trap the Philippines into reliance on dirty, deadly and costly fossil fuels at the expense of livelihood and biodiversity,” says Father Edwin Gariguez, winner of the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize and lead organiser of the “Protect VIP” campaign.

Furthermore, campaigners have pointed out that JBIC’s 2024 report on the LNG projects developed in Verde Island Passage admits to violations of Philippine laws.

The strong public backlash over association with fossil fuel financing and the accompanying adverse environmental and health impacts around such projects across APAC have already prompted some institutions to backtrack and divest.

“While other European investors have dropped San Miguel, UBS is holding on to its dirty investments. This means that Swiss money props up a company that keeps tightening the fossil fuel grip on its own country,” Frühwald explains. “UBS invests exclusively in the group’s bonds, which means it has no strategic influence. Any semblance of the ‘critical investor’ who contributes to decarbonisation is mere window-dressing.”

Asked what it would take for UBS to take action, the expert says: “For financial institutions like UBS, it is just about numbers on their balance sheet.”

“Yet behind every number lies a lived reality, such as that of Filipino fisherfolk communities who suffer daily from the impacts of fossil gas expansion in the Philippines, supported by financial institutions like UBS,” the expert added. “It is crucial that affected communities gain a strong voice in finance discussions. These stories must be told, and people must be placed at the centre of the conversation.”

UBS Can Change Course and Embrace the Role of the Climate Leader It Can Be

UBS is one of the global banks with the strongest traditions in climate action, having been among the first institutions to sign up to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) bank declaration in 1992. In 2002, it became a founding signatory of the Climate Disclosure Project (CDP), followed by its membership in various climate and sustainability-related initiatives, including the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (2015), the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative (2020) and the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (2021). Preserving its reputation requires continuing to exponentially reduce its financed fossil fuel emissions and halting any involvement, whether passive or active, in new fossil fuel project development taking place across Southeast Asia, as well as globally.

For UBS, it is now a case of walking the walk. Ensuring that sustainability communication aligns with the bank’s actions is not only a way to preserve its reputation and avoid public scrutiny, but also a mission to preserve the lives of some of the poorest, least responsible and most vulnerable to the climate crisis.

“You cannot be part of the solution if you still heavily finance the problem. Fossil fuel expansion must be a red line for both financing and investment portfolios. Companies that continue to expand their fossil business rather than phasing it down have clearly shown that they are unwilling to transform,” Frühwald notes.

On its website, UBS has compiled a dedicated guide for philanthropists and changemakers to address climate change, in which the bank discusses the toll of rising emissions on global warming and their uneven impact on communities from the Global South. No region embodies this better than Southeast Asia, and putting this blueprint into practice there is UBS’ best shot at restoring its reputation as the progressive bank, leading the global movement against climate change.

The past year has been the first in history to officially break the 1.5ºC temperature goal of the Paris Agreement — an early sign that the world is getting dangerously close to a future of irreversible planetary damage. And banks aren’t mere observers. Just the opposite: they are among the key enablers of the continuously-increasing emissions and, as such, can be the difference between a livable and a scorched world.

“Our planet’s lifeline is under threat, and leading these attacks are the fossil fuel companies enabled by the deep pockets of international banks,” Gariguez warns. “We urge UBS to cut ties with this dirty business.”

by Viktor Tachev

Viktor has years of experience in financial markets and energy finance, working as a marketing consultant and content creator for leading institutions, NGOs, and tech startups. He is a regular contributor to knowledge hubs and magazines, tackling the latest trends in sustainability and green energy.

Read more