Japan’s Updated NDC Plans Fall Short of Expectations

The National Diet Building in Tokyo. Source: Kakidai | Wikimedia Commons

20 February 2025 – by Walter James

Japan finalised and submitted its updated Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the United Nations on February 18, slightly later than the official February 10 deadline.

NDCs are countries’ plans to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to update their NDCs and “ratchet up” their ambitions every five years. Japan missed the February 10 deadline because the government was reviewing the 3,000 comments submitted during the NDC’s public comment period. But in the end, the finalised NDC featured the same unambitious emission reduction targets that the government proposed in late 2024.

Japan’s continued timidity in raising its climate and clean energy ambitions has its roots in its policy-making structure. For Japan to put forth truly ambitious GHG emissions reduction and clean energy strategies, fundamental reforms of its policy institutions are needed.

Japan’s Proposed Net-Zero Emissions Target

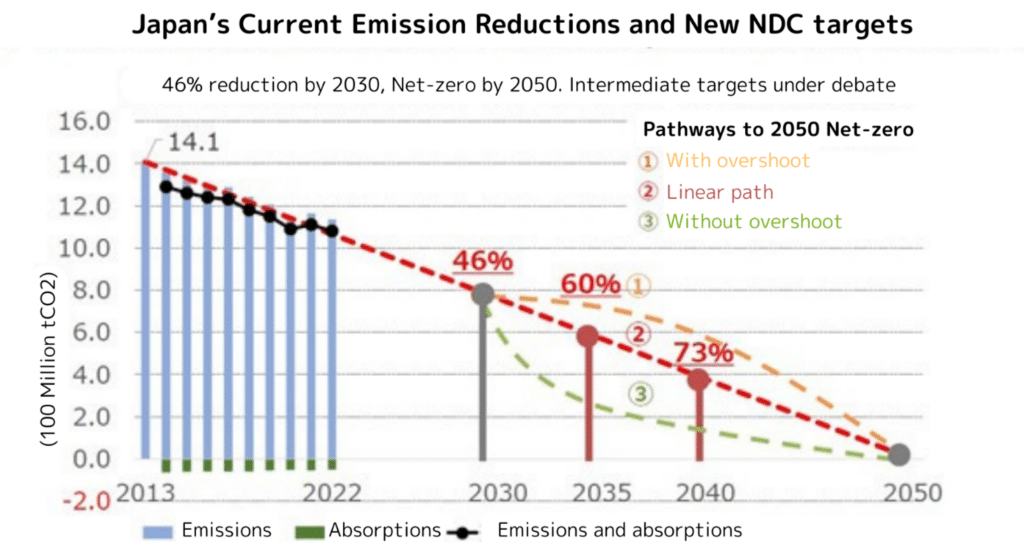

Japan — the sixth-largest emitter in the world — announced in 2020 its current emissions reduction target of 46% by 2030 compared to 2013 levels and net-zero emissions by 2050. With the deadline to update its NDCs looming in February this year, the economy and environment ministries jointly convened the Global Warming Countermeasures Working Group in June 2024. During its Nov. 25 meeting last year, the committee secretariat unveiled the proposed targets for the updated NDCs: 60% emissions reduction by 2035 and 73% reduction by 2040, both compared to 2013 levels. As the graph by the Tokyo-based Renewable Energy Institute shows, these targets are points on a straight line between the current target of 46% reduction by 2030 and net-zero by 2050.

Flawed Process and Misaligned Targets

As soon as the proposed targets were unveiled on Nov. 25, domestic and international observers began to put forth criticism that the proposed targets were not aligned with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal. The targets rest on a flawed interpretation of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report, which concluded that the world must reduce emissions by 60% by 2035 compared to 2019 levels to limit the probability of a 1.5°C warming scenario to less than 50%.

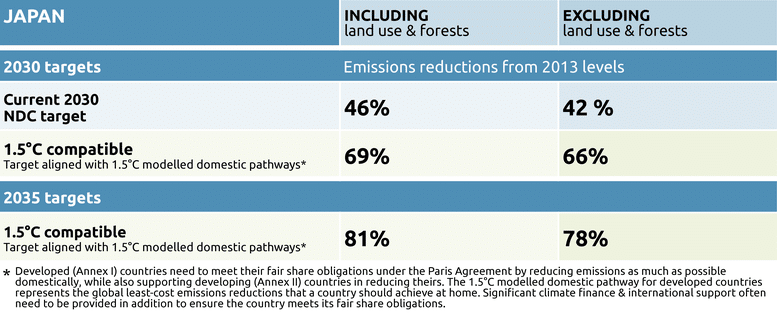

Accounting for the fact that Japan’s emissions reduction responsibility as an industrialised country is greater than the global average, and adjusting for 2013 as the baseline year (rather than the IPCC’s baseline of 2019) shows that Japan’s target must be much higher. Recent analysis by Climate Action Tracker finds that a reduction of at least 81% by 2035 below 2013 levels is needed for Japan to be 1.5°C-aligned.

Policy-making Structure of Japanese Government Remains Intact

Despite these criticisms, the government kept its proposed targets unchanged in its final NDC. That’s because Japan’s climate policy is subordinate to its energy policy, which in turn, is heavily influenced by incumbent interests.

“90% of Japan’s CO2 emissions come from its energy sources,” Hiroyuki Yasui, director of public policy at the Tokyo-based think tank Climate Integrate, told Energy Tracker Asia. “The most important part of its emissions reduction strategy should be how to reduce energy-related emissions.”

Japan’s energy policy is shaped by its Strategic Energy Plan (SEP), the comprehensive roadmap for the country’s energy system that the government revises every three years, rather than its climate targets. The economy ministry formulated the seventh SEP in parallel with the NDC.

Climate Integrate’s report published in June 2024 found that the expert committees under the economy ministry that discuss the SEP are skewed toward individuals representing high emissions and energy-intensive industries that are hesitant or ambiguous about the clean energy transition.

Research by InfluenceMap confirmed this finding. It concluded that, in formulating its climate and energy policies, “the government is primarily guided by the views of the Japan Business Federation (Keidanren), which in turn appears to be almost entirely guided by the views of a narrow group of sectors representing less than 15% of the Japanese economy.”

“If we consider that the SEP is what shapes the energy system, then how the SEP is discussed is very important,” Yasui said. “But the NDC committee can’t touch the SEP discussion, so the role of the NDC is quite limited.”

Impacts of Japan’s Climate and Energy Targets on Asia

Japan’s presence in the energy transition in the Asia-Pacific and Southeast Asia has grown in recent years.

A prominent example is the Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) that former Prime Minister Kishida initiated in March 2023 and includes 11 Southeast Asian countries and Australia. While AZEC’s stated mission is to help Asia decarbonise, recent analysis by Zero Carbon Analytics shows that over one-third of agreements signed under the AZEC framework are related to advancing fossil fuel technologies. These include gas and liquefied natural gas, ammonia co-firing with fossil fuel power plants, ammonia and hydrogen from non-renewable electricity and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCS).

The finalised NDC and SEP make it clear that Japan will double down on promoting these technologies abroad.

“Our worry is that the current strategies will continue the domestic development of hydrogen and ammonia co-firing and CCS to keep using coal-fired power plants,” Climate Integrate’s Yasui told Energy Tracker Asia, “and that these technologies will be promoted through AZEC.”

“If domestic policies change, the types of AZEC projects will also change.”

Reforms of the Structure Are Needed to Limit Global Warming

Yasui is clear on the kind of reform that is needed. He would like to see the economy ministry’s grip over energy policy loosened and for energy and climate strategies to be formulated together by an independent body.

“The jurisdictional boundaries between the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of the Environment should be dissolved, and something like a ‘Climate and Energy Ministry’ should be created to facilitate integrated discussions on climate change measures,” he explained.

by Walter James

Walter James is the principal consultant at Power Japan Consulting, which offers research, writing, and consulting services related to Japan's climate and energy policies. He also writes about these topics on his Power Japan Substack. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Temple University and is a former research fellow at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.

Read more