No Progress on the Global Stocktake at COP30

19 November 2025 – by Viktor Tachev

The first Global Stocktake, a five-year process for tracking the collective progress toward the goals of the Paris Agreement, was concluded at COP28 in 2023. The results identified significant gaps in global climate policies, climate finance provision and emissions reduction levels. According to the UN, the process “outlines bold actions for Governments and stakeholders to urgently undertake in this critical decade to keep 1.5 within reach, securing lives and livelihoods.”

At the time, there was hope that the findings and the evident lack of progress in limiting global warming to 1.5°C compared to preindustrial levels would inform and inspire governments to accelerate ambition and enhance their climate action plans. Unfortunately, two years later, the situation appears to be worse.

At COP30 Brazil, Two Years After the First Global Stocktake: The 1.5°C Target Now ‘Virtually Impossible’ Despite Major Progress

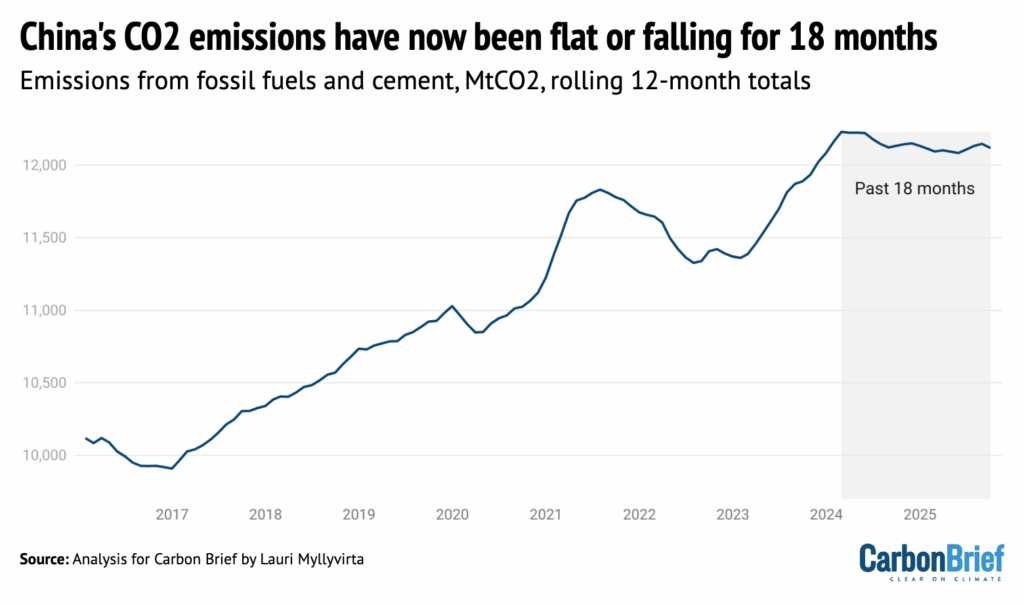

The Paris Agreement has been a significant success in motivating public and private sector stakeholders to take action to mitigate emissions. For example, China’s emissions have now been flat or falling for 18 months, according to Carbon Brief, mainly due to electricity generation from solar growing by 46% and wind by 11% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2025.

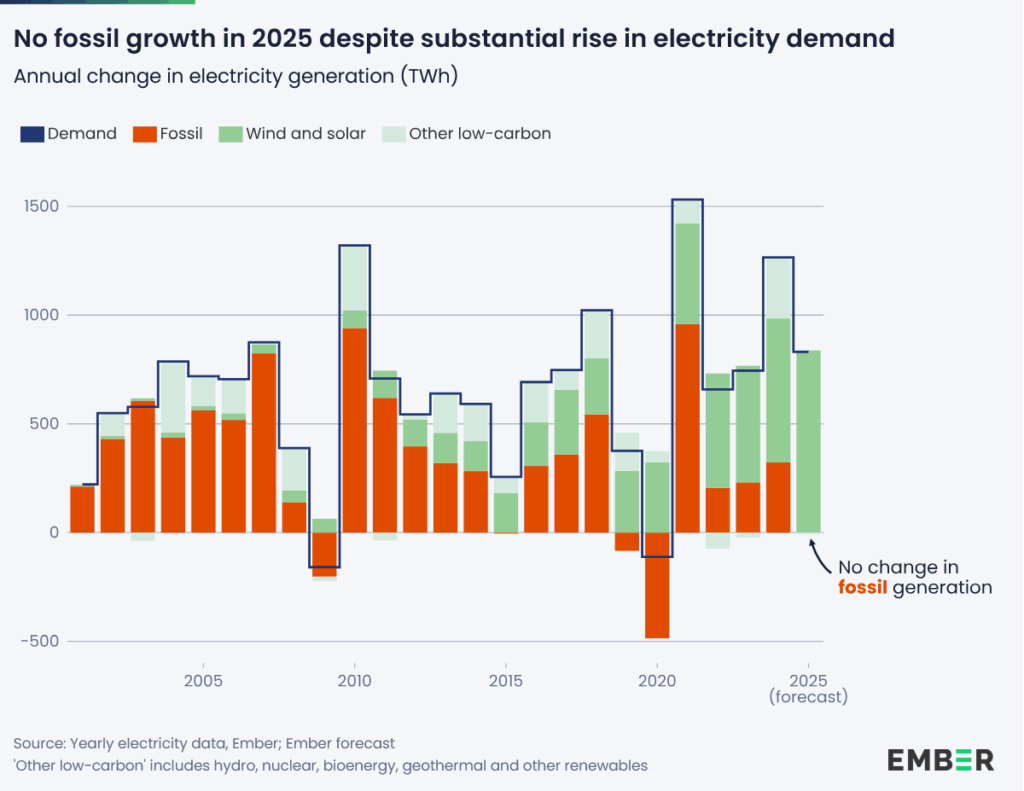

Furthermore, Ember finds that solar and wind growth met all new electricity demand in the first three quarters of 2025. The experts say they don’t expect an increase in fossil fuel use this year.

Last but not least, polls have shown that global business leaders are overwhelmingly in favour of government action on a rapid transition, with 97% of business executives across 15 major economies supporting the shift away from fossil fuels to renewable energy. As much as 78% advocate for this to happen within 10 years, as they recognise that a delay means missing out on investment, jobs and competitiveness.

However, despite all these positive developments, in an interview before the start of COP30 Brazil, UN Secretary-General António Guterres announced that humanity has missed the 1.5°C climate target, which he described as a “moral failure” and warned of devastating consequences. Similar warnings also came from the UN Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organization, with both saying that the target was now unachievable. Among the reasons behind such statements are the following.

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) Increasingly Unambitious

According to Climate Action Tracker’s November 2025 update, there has been little to no measurable progress in warming projections for the fourth consecutive year. As a result, the world is on course for a 2.6°C global warming trajectory.

While this marks major progress since the Paris Agreement, when the world was on a 3.6°C warming trajectory by 2100, we are still facing dangerous consequences. Experts note that 2023, 2024 and 2025 have been the three hottest years in 176 years of records, while the past 11 years, from 2015 to 2025, are also set to be the 11 warmest years on record.

A world this hot could trigger major “tipping points” that could cause the collapse of key Atlantic Ocean circulation, the loss of coral reefs, the long-term deterioration of ice sheets and the conversion of the Amazon rainforest to a savannah, said Bill Hare, CEO of Climate Analytics. “That all means the end of agriculture in the UK and across Europe, drought and monsoon failure in Asia and Africa, lethal heat and humidity,” Hare said.

According to CAT, the 2035 NDCs submitted so far don’t change the dial in terms of keeping warming to 1.5˚C, noting that almost none of the 40 governments analysed have updated their 2030 targets.

The findings come despite WMO’s conclusion that, in 2024, the levels of CO2 in the atmosphere soared by a record amount, hitting a new high. Furthermore, scientists are now concerned that natural CO2 sinks, such as oceans and land, are weakening due to global warming, posing a significant risk that the global climatic system will enter a vicious cycle where temperatures rise even faster.

Renewable Energy Capacity Outside China Marks Sluggish Growth

There is no doubt that the green energy transition is happening and is inevitable. Since the Paris process began, global renewable energy capacity has increased by 140%, while clean energy investments outpace fossil fuel investments 2:1. Renewables have become the most cost-effective power source, and over 90% of global GDP is now covered by net-zero pledges.

However, the problem is that the global clean energy transition is not happening fast enough.

Ember finds that, two years after parties at COP28 united behind the task to triple renewable energy capacity by 2030, global renewable targets for the end of the decade are up by just 2%. According to the analysts, national renewable energy targets collectively now add up to 7.4 TW for 2030, which is far from the 11 TW the goal requires. As a result, countries are currently aiming only for a doubling of capacity by 2030, with the gap to the COP28 target remaining “stubbornly wide”.

Financing For Developing Nations to Accelerate Climate Action is Lacking

The 2025 UNEP Adaptation Gap Report reveals that developing countries will require at least USD 310 billion annually by 2035 to adapt to climate change. For reference, this represents 12 times the current international public finance flows.

The report also warns that, based on current trends, the Glasgow Climate Pact goal to double adaptation finance to around USD 40 billion by 2025 will not be met, putting millions at greater risk from floods, heatwaves and storms.

According to the UNEP, it is now critical for countries to deliver USD 1.3 trillion from both public and private sources by 2035 to meet adaptation finance needs.

“The finance gap is not just a number, it’s a reflection of the growing risks to people’s health, safety and dignity. From heatwaves that strain healthcare systems to floods that contaminate water supplies, the impacts are intensifying, and the most vulnerable are paying the highest price,” notes Dr. Jemilah Mahmood, a professor and executive director of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health at Sunway University in Malaysia. “We need urgent, scaled-up adaptation finance that prioritises grants and concessional support, not more debt. Climate resilience must be built on fairness, care and global solidarity.”

Despite the lack of progress in scaling up climate financing, analysts note that all three of the New Collective Quantified Goals (NCQGs) — mobilising at least USD 1.3 trillion per year by 2035 by all actors from public and private sources, at least USD 300 billion mobilised from public, private, bilateral and multilateral sources, with developed nations taking the lead, and at least triple the annual outflows from UNFCCC climate funds from 2022 levels by 2030 — are achievable with commitment and cooperation from governments, international institutions and the private sector to scale up finance and reform systems to make climate finance more effective.

Fossil Fuel Lobby Continuing to Undermine the Global Climate Action

The central scenario of the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2025 report, released during COP30 UN climate change conference, predicts that oil and coal demand will peak by or before 2030, while global gas demand will rise by 10% from current levels. This raises questions about the new planned fossil fuel capacity, notably the major gas expansion plans across Asia. Currently, new fossil fuel projects continue to come up, with the global fossil fuel output in 2030 more than double what we can safely burn under the Paris Agreement’s temperature goals.

In every single scenario in the IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2025 report, including the one where the world halts climate action, renewables grow faster than any other energy source due to their competitiveness.

“Some may wish to turn back the clock, but the direction of the energy system is clear. The electricity age is well underway,” says Laurence Tubiana, CEO of the European Climate Foundation. “The choice now is between accelerating or paying later to undo the damage: every tonne of carbon we avoid today saves far greater costs tomorrow. We can keep looking backwards and burying our heads in the sand — or look forward, clear-eyed, to the future we must build to avoid catastrophe.”

The IEA’s World Energy Outlook 2025 report notes that it is still possible to limit global warming to 1.5°C, but for this to happen, the world needs to stop deploying new fossil fuel projects and gradually phase out existing capacity.

However, the fossil fuel lobby continues to undermine progress and act against scientists’ warnings, including at COPs. Research reveals that more than 7,000 fossil fuel lobbyists gained access to the UN climate summits in the past five years to block progress on climate talks. Last year alone, the registered fossil fuel lobbyists for COP29 in Azerbaijan were 70% more than the total number of delegates from the 10 most climate-vulnerable nations combined. Over 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists attended the COP30 climate negotiations in Belém this year, significantly outnumbering the delegations of every single country apart from the host, Brazil, and representing a 12% increase from last year’s climate talks.

Furthermore, according to data from Urgewald’s Global Oil & Gas Exit List, 96% of upstream oil and gas companies are still exploring or developing new resources. In total, the industry is planning 33% more short-term expansion today than it was in 2021, when the IEA stated that no new oil and gas fields are necessary to meet oil and gas demand in a 1.5°C world.

“The world’s biggest oil and gas companies are treating the Paris Agreement like a polite suggestion, not a survival plan,” comments Nils Bartsch, Head of Oil and Gas Research at Urgewald.

According to the experts, the industry spends around 75 times more each year on exploration than governments have currently pledged to the UN Loss and Damage Fund, which is meant to help countries already suffering from climate disasters.

Furthermore, the past three editions of COP were all held in petrostates or countries with vested interests in maintaining the status quo.

This year’s host, Brazil, was considered a breath of fresh air due to its seemingly ambitious climate agenda. In his opening speech at the Belém Leaders Summit, Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced that COP30 would be a “moment of truth”: truth on facts, science, and actions. Yet, an investigation has revealed that the Brazilian government is also pushing ahead with fossil fuel projects, including an oil license granted less than a month before COP30 in the Amazon River basin.

“Brazil is showing an alarming level of climate hypocrisy — presenting itself as a climate leader at COP30 while allowing oil and gas expansion right at the summit’s doorstep, threatening one of our most fragile ecosystems,” says Nicole Oliveira, Executive Director of the Arayara International Institute in Brazil.

The move contradicts the global scientific consensus around climate change and also defies recent rulings from the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the International Court of Justice, which reaffirm states’ legal duty to halt fossil fuel expansion and protect the climate.

“We have said it before, and we will keep saying it: we are running out of time,” said Sofia Gonzales-Zuñiga from Climate Analytics. “Every new fossil gas deal the EU makes, every new coal plant built in China, every fossil gas expansion project in Australia, every exported barrel from Norway, every tonne of LNG Japan pushes into neighbouring Asian countries, costs billions to people elsewhere in the world as they deal with increasingly extreme weather events. These are not abstract policy choices — they are physical realities with human consequences. The atmosphere does not negotiate, and it does not wait.”

Experts also identify US President Donald Trump’s policy of climate change denialism — also criticised by delegates from islands facing extinction during COP30 — as a major obstacle to accelerating emissions reduction efforts. According to David Tong, global industry campaign manager at Oil Change International, the US is attempting to derail the global mission to limit warming to 1.5°C, “the only route to survival,” by continuing business as usual and reviving an outdated, fossil-fueled scenario.

“We can protect people and communities by aiming for 1.5ºC, settle for a disastrous business-as-usual 2.5ºC or choose to backslide into a nightmare future of much higher warming,” he warns, urging leaders to oppose Trump’s “dystopian future”. “At COP30, governments must reject this nightmare fantasy, uphold a just transition, and choose a fast, fair and funded fossil fuel phaseout.”

The COP30 Energy Day Developments Failed to Instil Optimism For Global Stocktake Progress

Discussions on climate finance and the ambition to pursue the 1.5°C target marked the first week of COP30 2025. Regarding financing, a key development was the fund for responding to climate change-caused loss and damage, launching its first call for project proposals, with an initial package totalling USD 250 million. Furthermore, parties are expected to make progress on the “Baku to Belém roadmap,” exploring how to ramp up finance up to the agreed-upon USD 1.3 trillion by 2035. COP30 CEO Ana Toni stressed that the financial resources needed to implement climate action already exist, noting that it was a question of redirecting them “at the scale and speed required to tackle the climate crisis”. However, it remains unclear whether governments will take the roadmap forward beyond COP30.

Furthermore, South Korea announced it will join the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), aligning itself with other climate-progressive economies. The country became the first in Asia with an operating coal plant fleet to formally commit to a coal phaseout, putting pressure on other coal-heavy economies in Asia and G20 peers.

During the thematic days, dedicated to the energy transition, 23 countries, as well as corporate sector stakeholders, also agreed on the “Belém 4X” statement, aiming to quadruple the use of sustainable fuels by 2035. However, as per the definition, sustainable liquid and gaseous fuels are also considered “sustainable”.

Furthermore, grid and storage technologies also saw traction. Utilities committed nearly USD 150 billion annually to clean energy grid and storage expansion, while multilateral development banks (MDBs) launched various regional investment platforms. The Global Grids and Storage Coordination Council, supported by the Climate Finance Principles for Grids, set a unified direction for improving energy access.

Aside from these, however, delegates didn’t deliver noteworthy developments regarding the energy transition, which is typically the case, as evident from previous COPs, where any major wins or failures are often negotiated in the final minutes of the conference.

Still, at the time of writing, there are positive signs that COP30 might deliver stronger language on fossil fuel phaseout. For example, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s call for a “roadmap” away from fossil fuels ahead of COP’s opening, there has been increased traction in how such a mechanism can take shape, including a new declaration by Colombia and a roadmap with backing from several countries, including Denmark, the UK, France, Kenya and Germany, floated as possible options.

Marina Silva, Brazil’s environment minister, continued to push actively for a fossil fuel phaseout throughout the first week of the conference. However, she noted that the process would be voluntary for those governments that wished to participate, and “self-determined.” So, it remains to be seen if the minimal chance for such a deal materialises by the end of COP30.

Still, reaching a deal for all countries to contribute to a “transition away from fossil fuels” and implement the Global Stocktake outcomes as per the COP28 agreement remains a long shot. According to a draft text from Nov. 13, countries remained in disagreement on many key topics nearly halfway through the summit.

Next Steps: The Global Stocktake During and After COP30 2025

While scientists are increasingly in consensus that the 1.5°C target is now out of reach, stakeholders from the public and private sectors need to accelerate efforts to mitigate global warming and minimise the rise, as the lower the temperature increase, the fewer the adverse impacts on economies, ecosystems and livelihoods. A key measure on that front would be achieving the global target of tripling renewable energy capacity by 2030, as agreed upon at COP28, as well as phasing out fossil fuels as soon as possible.

However, scientists warn that even if the world succeeds with these ambitious targets, it still won’t be enough to bring temperatures back down to 1.5°C by the end of the century. Instead, we would have to invest in sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere, including nature-based solutions like growing forests and wetlands, as well as technologies for removing and storing it.

Furthermore, it is imperative to agree to cut methane emissions, the single biggest contributor to short-term warming, and a driver of at least a third of the warming in recent years. According to experts, global temperature rises could slow down by about 0.3°C in the next decade with a 40% cut in methane, or by as much as 0.5°C by 2050 with further cuts. Furthermore, cutting methane emissions by a third by 2030 would unlock approximately USD 1 trillion per year for the global economy.

While the magnitude of the challenge is enormous, it is achievable if governments and public sector stakeholders get on board with the task. This, however, is a big “if” as fossil fuel interests and climate change denialism are still growing strong, silencing even the loudest voices from concerned scientists and vulnerable communities. This means a handful of nations, corporations and financiers are holding the world hostage over an existential threat that we have the tools to address without sacrificing economic growth.

To ensure a livable future for the next generation, public and private sector stakeholders must unite and work to urgently phase out fossil fuels, halt and reverse deforestation and scale up renewable energy sources. As recent court rulings have shown, the 1.5°C temperature limit is now a legally binding threshold, meaning governments and corporate polluters have a legal obligation to halt emissions.

In that sense, choosing anything other than reducing emissions and halting pollution means governments and corporations will face serious repercussions in both the court of law and public opinion. Still, none of that will matter to the victims of an existential threat that is already claiming a life every single minute.

by Viktor Tachev

Viktor has years of experience in financial markets and energy finance, working as a marketing consultant and content creator for leading institutions, NGOs, and tech startups. He is a regular contributor to knowledge hubs and magazines, tackling the latest trends in sustainability and green energy.

Read more