A Close Look at China’s Five Year Plan for Coal (2021-2025)

10 November 2021 – by Aiqun Yu

2021 is a big year in China. It’s the beginning of the 14th Five Year Plan or FYP. Every five years, the entire government system begins a campaign of planning from the ground up, from sports to education to weather forecasting. Since the sixth FYP from 1981 to 1985, these plans have successfully guided China through 40 years of rapid economic growth.

However, regarding energy sourced from coal, the 14th FYP that came out in March 2021 did not offer any clear, practical indicators like the plan’s predecessors. For example, five years ago, a cap of 1,100 GW on coal power was written into China’s 13th plan, and by 2020 coal capacity reached 1,080 GW – mission accomplished.

In China, coal is the anchor for the country’s energy and supplies around 70% of its electricity, along with 43% of its carbon emissions. Recently, China has promised to limit coal growth, including strict controls during the 14th FYP period. By 2030, the country hopes to reach a peak in carbon emissions and end financing overseas coal projects. But the world is still nervously questioning just how much coal will be added during this time in China domestically by 2025.

China’s Coal Plan and Conflicting Permits

According to the Global Coal Power Tracer, or GCPT, by Global Energy Monitor, 140 GW of coal capacity has either been permitted for contraction or is already under construction – with an extra 163 GW proposed. Just how many of these carbon dioxide-spewing plants will be built is anyone’s guess.

To get a rough idea, I dove into China’s 31 provinces’ individual FYPs. It’s well known already that there are tensions between provincial governments and the central government over coal-powered development. Essentially, the despite revolves around local governments wanting to boost coal output to raise GDP and generate jobs. However, facing international pressure, China’s central government is not favouring these policy approaches proposed by the provincial governments.

With this, the central government has tried to restrain the impulses of the provinces but conversely also has to ensure energy security and economic growth. To reiterate this, the central government mentioned coal in one short sentence in the 14th FYP: “合理控制煤电建设规模和发展节奏” – to reasonably control the scale and momentum of coal power development. The provincial governments, however, were more explicit.

After reviewing these provinces’ FYPs, three surprises dawned on me. The first is that traditional big coal provinces have little appetite for new coal capacities, at least on paper. For example, the province of Inner Mongolia, home to China’s second-largest coal capacity, did not even mention coal power additions in its FYP. The same went for Shaanxi, Xinjiang, and Shandong, all provinces that are rich in coal deposits.

In Shandong, though, there are plans to help construct new coal power plants in other provinces on the condition that some of the power is sent back via UHV lines combined with renewable energy.

There was a similar story in Shaanxi, where the province played a numbers trick. In its FYP, Shaanxi is planning for a total power capacity of 136 GW by 2025. It states that 65 GW will be sourced from renewables, leaving 71 GW for “non-renewable” sources. With Shaanxi’s current coal capacity at 45 GW with another 13 GW under construction, the math is straightforward on just how much is left over for other coal projects.

Together, the provinces mentioned above make up 72.2 GW of coal power capacity that’s either permitted or under construction. According to GCPT, this accounts for half of China’s total capacity. It’s clear that these provinces know about coal’s bad reputation and don’t want to support it – at least explicitly on paper.

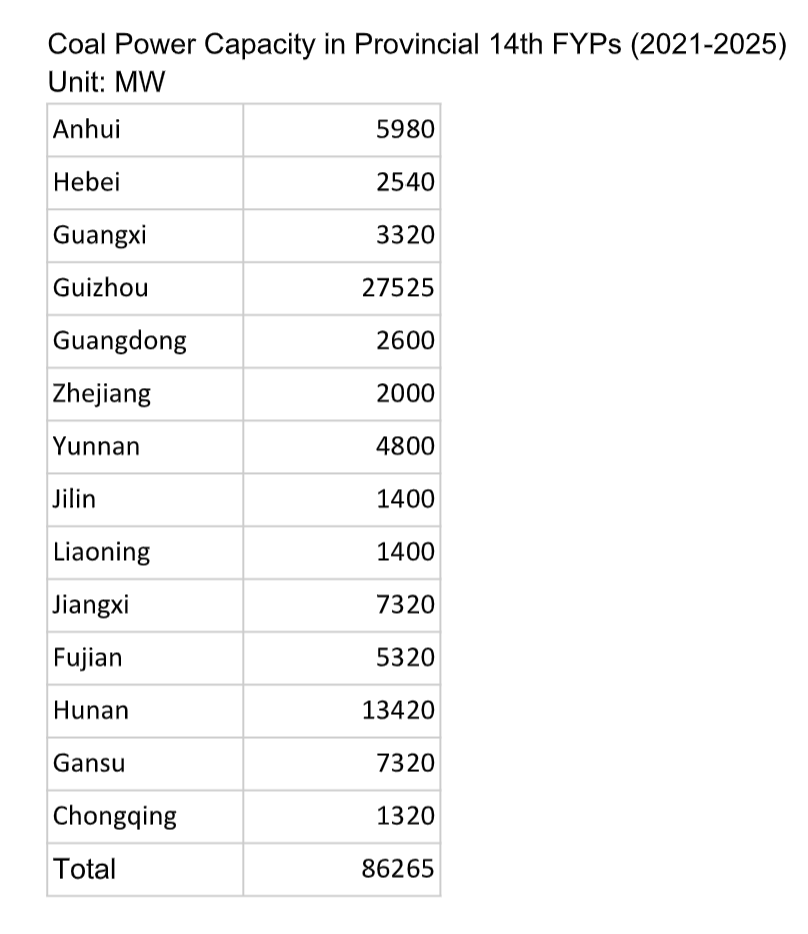

Elsewhere in China, 14 other provinces – including municipalities and autonomous regions – list specific coal power projects in the FYPs. These projects total 86 GW. Amongst these, 36 GW are already permitted for construction or under construction, with an extra 50 GW in the preparation stages. This means that after the permit rush in the last year of the 13th FYP, 50 GW of coal power is likely to be given the green light over the next five years.

Among these 50 GW of coal power proposals, 10 GW were abandoned before being retrieved in the FYP, including 4.8 GW in Yunnan, which is surprising. Yunnan province in China’s Southwest is a hydropower rich region, and coal only accounts for around 15% of its total capacity. Over the years, several industries like aluminium, which are traditionally heavily reliant on coal power, suffered from stricter emissions controls in other provinces, swamped Yunnan. This was in part because of cheap hydropower and lax environmental regulations. However, in the first half of 2021, hydropower’s generation dropped significantly from declining snow and rain in winter, leading to a revival of these “cancelled” coal power projects.

Finally, the third and largest surprise was in Guizhou, ranking at 22 out of 30 provinces for GDP. In the past, it was one of China’s poorest regions, and even today, many people in its mountainous regions still use firewood for fuel. Guizhou’s economic growth has been rapid but is heavily reliant on intensive industries. It is hoping that its deposits of lignite coal – or brown coal, which is considered one of the dirtiest versions of coal – will help drive more economic growth with an increase in 27.5 GW of coal power projects in its FYP.

While the central government still has the last word on what projects are permitted, putting everything together begs the question of whether the opportune moments ever come for these coal projects and whether China will allow it to continue? We have to wait and see what’s to come of China’s coal plan.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About Global Energy Monitor

Global Energy Monitor develops and shares information on fossil fuel projects in support of the worldwide movement for clean energy. Current projects include the Global Coal Plant Tracker, the Global Fossil Infrastructure Tracker, the Europe Gas Tracker, the CoalWire newsletter and the GEM wiki.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Energy Tracker Asia.