Japan’s Overseas Oil and Gas Financing Threatens the Global Energy Transition

Photo: Shutterstock / VladSV

26 September 2024 – by Walter James

Japan’s oil and gas financing was responsible for the construction of the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) production project in Indonesia. Producing 11.4 million tonnes of LNG per year, the Tangguh LNG Project supplies one-third of Indonesia’s LNG. The USD 1.2 billion loan from the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) catalyzed investments from a host of other Japanese public and private-sector companies. Some of the LNG produced at Tagguh is shipped to Japan, with some of it fuelling the Jawa-1 power plant that began operations in Indonesia in March 2024. JBIC was also a key player behind the financing of the 1,760-megawatt (MW) Jawa-1 electric generation plant.

Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC)

JBIC and its partners praised Tangguh for contributing “a steady supply of LNG for Japan” and Jawa-1 as a “power source for sustainable electricity supply” to meet Indonesia’s surging energy demand. What they didn’t mention was that the carbon emissions and methane leaks from these projects would worsen the climate crisis. They also neglected to explain that renewable energy sources would have genuinely contributed to Indonesia’s clean energy transition at a lower price tag.

Jawa-1 and Tangguh were just two out of the 141 fossil fuel projects worldwide that the Japanese government financed over the last decade. A new report by the South Korea-based think tank Solutions for Our Climate (SFOC) titled “Billions Off Course: Japan’s Oil and Gas Financing Fueling the Climate Crisis” gives a detailed look into the fate of these investments.

Japan’s Persistent Overseas Oil and Gas Financing

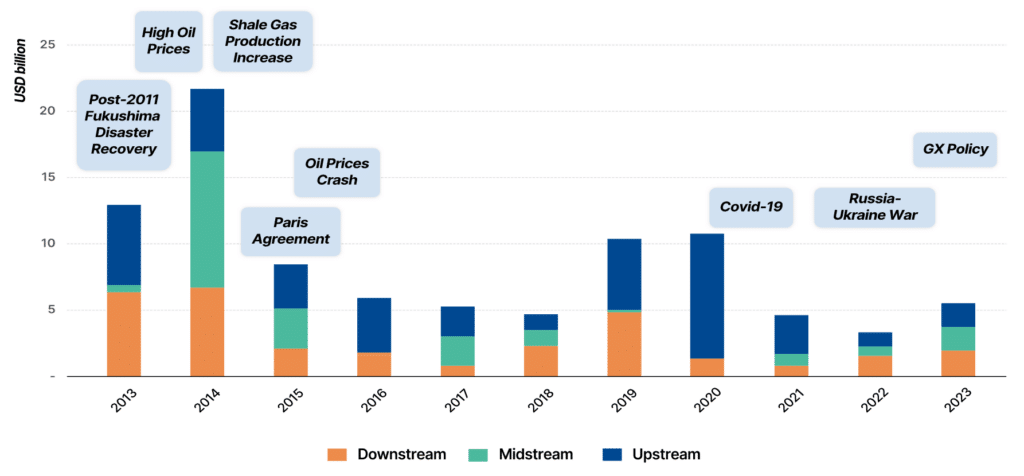

SFOC’s report details the trends of financing provided for international oil and gas projects between the fiscal years 2013 and 2023 by five Japanese public institutions: JBIC, Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC), Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) and Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA).

The report’s analysis offers several notable takeaways. Between 2013 and 2023, the Japanese institutions in total spent approximately USD 93 billion on oil and gas projects across the world. In contrast, they invested only USD 24.5 billion in clean energy over the same period, amounting to merely one-fifth of the total fossil fuel financing and paling in comparison to the global need of over USD 4 trillion annually by 2030 to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

This trend has continued recently, even after Japan joined a Group of Seven agreement in 2022 to stop overseas fossil fuel financing. Between 2020 and 2022, Japan doled out an average of USD 6.9 billion per year, the third largest source of fossil fuel finance after Canada and South Korea.

The recent increase in Japan’s public financing for oil and gas projects was driven by the Russia-Ukraine war and the introduction of Japan’s Green Transformation (GX) policy. The eruption of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022 disrupted global energy markets. In response, Japan boosted its investments in upstream projects, leading to an upward trend in financing. This included doubling down on securing stable LNG supplies by providing commitment lines for Japanese corporations to support overseas procurement. The GX policy, formalized in 2023, also promotes investments in upstream gas development and LNG power generation.

The report also shows that investments in gas infrastructure account for 60% of Japan’s total fossil fuel financing, and that the projects in the upstream segment of the supply chain — including exploration, drilling, extraction and production — received the largest portion, at 45%.

Energy Security, Corporate Interests and Asia’s Energy Transition

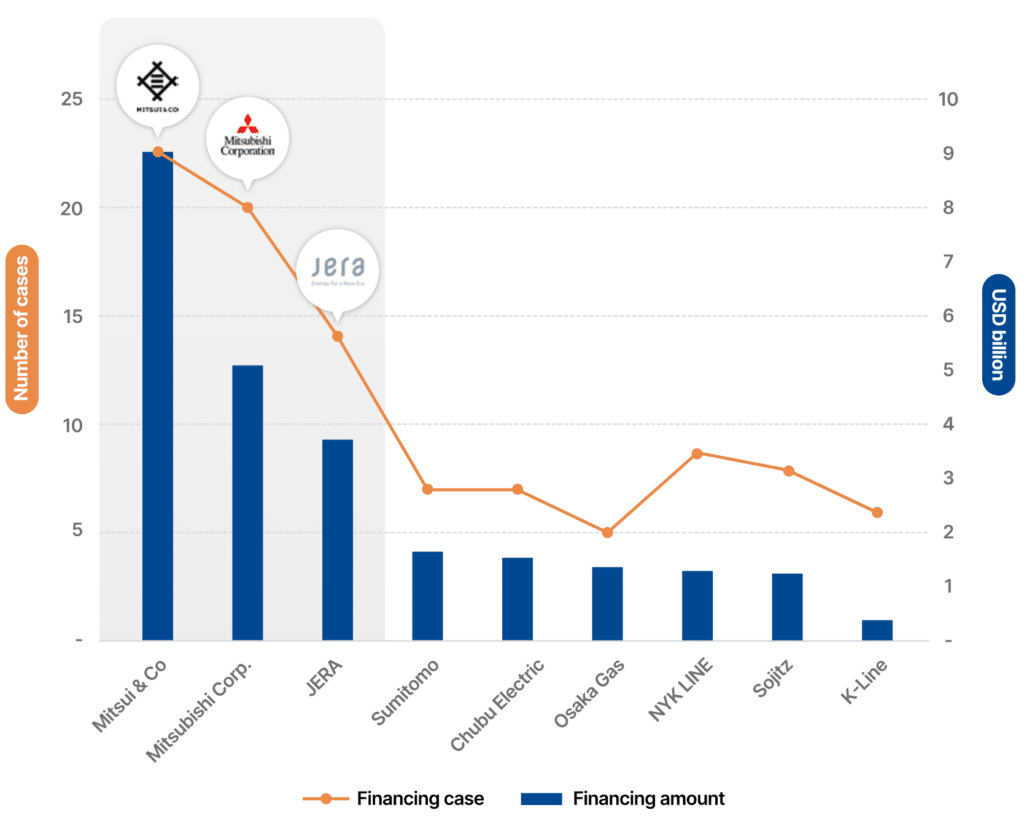

SFOC’s report also identifies the Japanese government’s justifications for it continuing oil and gas financing abroad. The first is the need for Japan’s energy security through stable supplies of oil and gas. This is why upstream financing has historically accounted for the largest portion of its overall investments.

Another justification is to promote Japanese corporate interests by expanding foreign markets for their technologies and positioning them as the leading firms in the regional LNG market. This second rationale explains the recent uptick in downstream projects — oil refining, petrochemical manufacturing, city gas and power generation — that drive demand for oil and gas in overseas markets. LNG power plants, like the Jawa-1 project, fit squarely into this agenda.

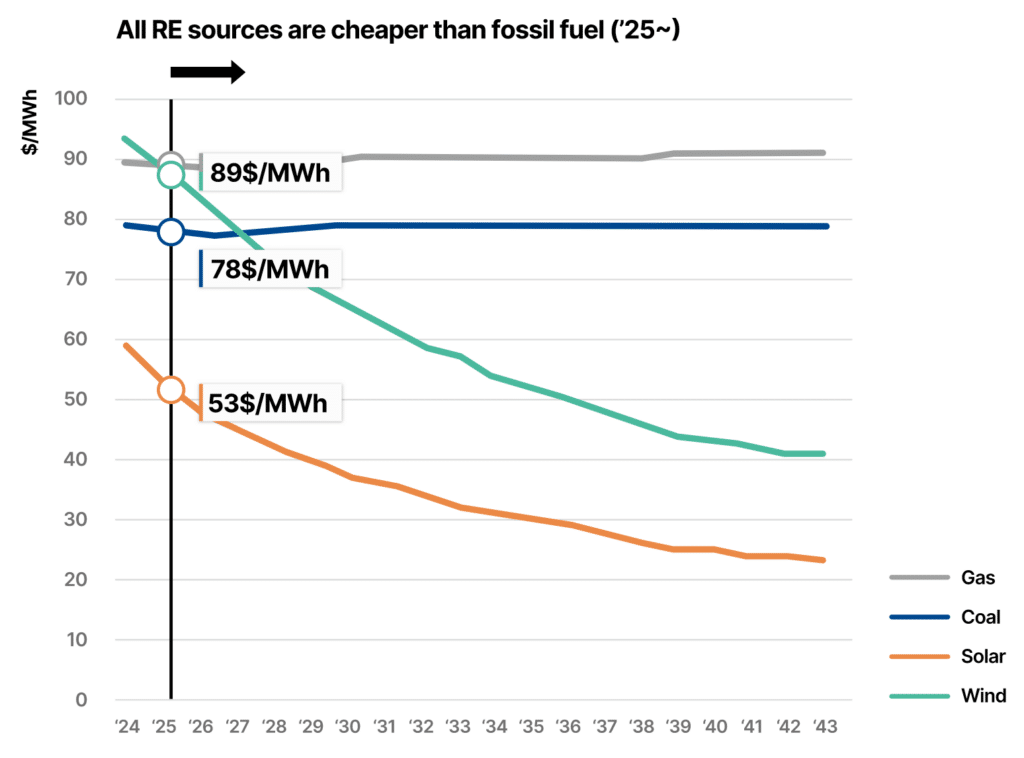

Japanese institutions also purport to assist South and Southeast Asia with their energy transition by promoting LNG to wean away from coal. But the rapidly improving economics of renewable energy renders this claim untenable. Globally, renewables — especially utility-scale solar — have emerged as the clear solution for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions, improving energy access and strengthening energy security. The Asia-Pacific region is no exception. The levelised cost of electricity from renewable sources declined significantly over the last few years, whereas the costs of coal and gas generation have risen. In 2023, renewables were 13% cheaper than conventional coal in Asia and are expected to be 32% cheaper by 2030.

Risks Abound

Not only do oil and gas investments no longer make economic sense, these investments imperil the climate, the energy transition in Asia and Japanese companies and their investors.

These investments have worrying ramifications for the climate crisis. Although often touted as a “transition fuel”, gas is in fact responsible for significant amounts of methane leaks, a greenhouse gas with a global warming potential 34 times stronger than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period and 86 times stronger over 20 years.

Japanese investments in the gas supply chain also threaten to derail Asia’s energy transition and expose host countries to both financial and geopolitical risks. At the same time as the costs of renewables are falling, the costs of new gas power projects are rising. These unnecessary costs will eventually need to be shouldered by either the project operators — including many Japanese players — or South and Southeast Asia’s electricity consumers. These countries also experienced destabilizing fuel price spikes after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Japanese investments promoting one volatile fossil fuel — coal — for another — gas — cast doubt over Japan’s intentions with its allies in the region.

The worsening economics of fossil fuels also pose risks for the Japanese financiers and project developers. Despite gas demand predicted to fall, many new gas and oil projects are expected to come online, mainly in Qatar and the US. These projects will likely cause a supply glut, threatening the profitability of Japanese energy companies that are already finding themselves over-contracted.

Stop Fossil Fuel Financing

To address the climate crisis and to genuinely contribute to Asia’s clean energy transition, Japan must halt its overseas fossil fuel financing.

SFOC’s report highlights several practical steps that Japan should take to honor its net zero commitment. First, the Japanese government must announce restrictions on all global oil and gas financing, including for projects set to use technologies designed to prolong the life of fossil fuel plants like carbon capture and storage, hydrogen and ammonia. Instead, those enormous investments that currently flow to oil and gas must be redirected to renewable energy projects globally.

Second, the Japanese public financial institutions must be required to disclose detailed information about their activities and the financing extended to energy-related projects. Transparent disclosure would ensure their accountability to Japan’s international pledges and allow for independent assessments of these institutions’ potential impact on the climate.

If these measures were in place, Japanese funding for the Tangguh LNG Project and the Jawa-1 LNG power plant would not have passed scrutiny as clean energy financing. Instead, Japan can become a leading financier of true clean energy projects, making a meaningful climate impact in Asia and across the globe.

by Walter James

Walter James is the principal consultant at Power Japan Consulting, which offers research, writing, and consulting services related to Japan's climate and energy policies. He also writes about these topics on his Power Japan Substack. He holds a Ph.D. in Political Science from Temple University and is a former research fellow at Waseda University in Tokyo, Japan.

Read more