Green Bonds: Sustainable Financing Tools or a Greenwashing Weapon?

Photo by Jamesteohart

22 September 2022 – by Viktor Tachev

Green bonds enjoy strong interest from governments, development banks, the private sector and the bond market.. However, sustainable financing mechanisms are a double-edged sword. They can either speed up the global decarbonisation effort and provide environmental benefits or serve as an effective greenwashing tool. Regulatory changes are the only way for green bonds to fulfil their mission and ensure that investors’ capital moves towards sustainability-aligned causes and is not purposed for giving fossil fuels a lifeline.

What is a Green Bond?

A green bond is a type of debt instrument that is used to finance environmental projects. The proceeds from the sale of green bonds are used to fund new and existing projects with positive environmental impacts, such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, and pollution reduction.

The green bond market has seen rapid growth in recent years. The World Bank is one of the leading issuers of green bonds.

Green Bonds Issuance is on the Rise

Green bonds, also known as climate bonds, help governments and corporations gather and direct financing to projects with positive climate and environmental outcomes.

Climate Bonds Initiative and the Green Bond Market

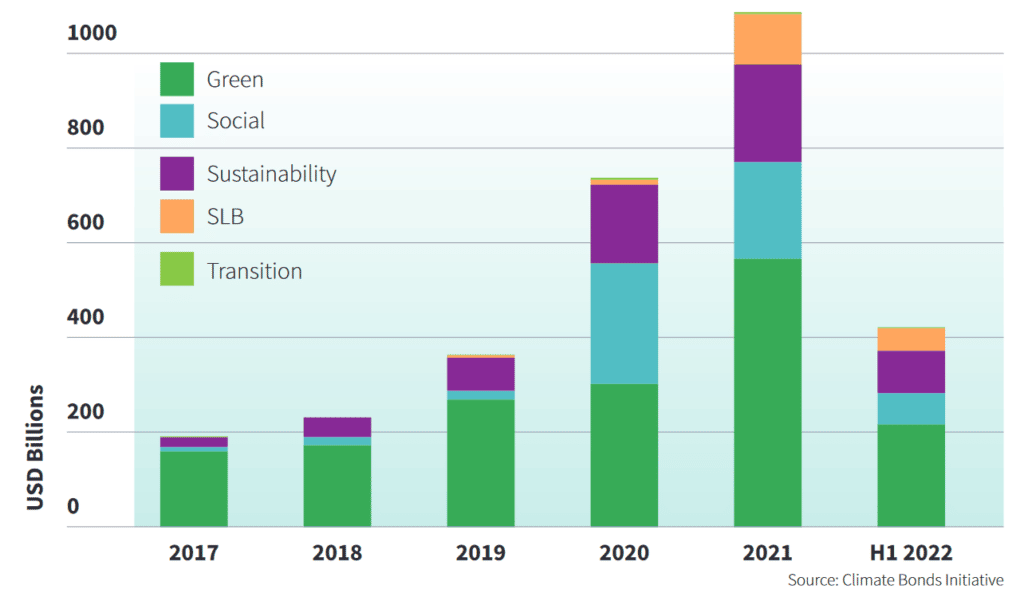

Since the first green bond was issued in 2007, the green bond market has been on a steady upward trajectory. In 2020, it surpassed the USD 1 trillion mark. The entire GSS (green, social and sustainability) bonds market topped USD 1.7 trillion.

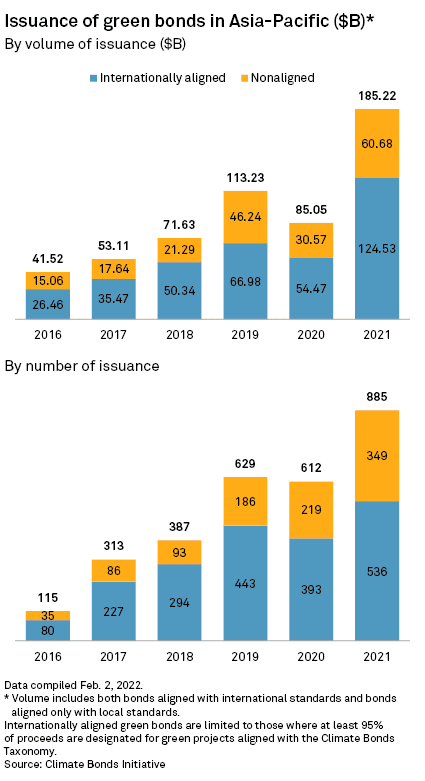

Asian countries are among the bond issuers showing the most substantial growth. In 2021, the ASEAN market reached record highs, marking a 76.5% year-over-year increase. Corporate issuers were the main driver behind that growth.

The Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) latest report finds that this growth has slowed down in H1, 2022. Among the key factors were the Russia–Ukraine war, the energy crisis and the exacerbated inflation, impacting global bond markets.

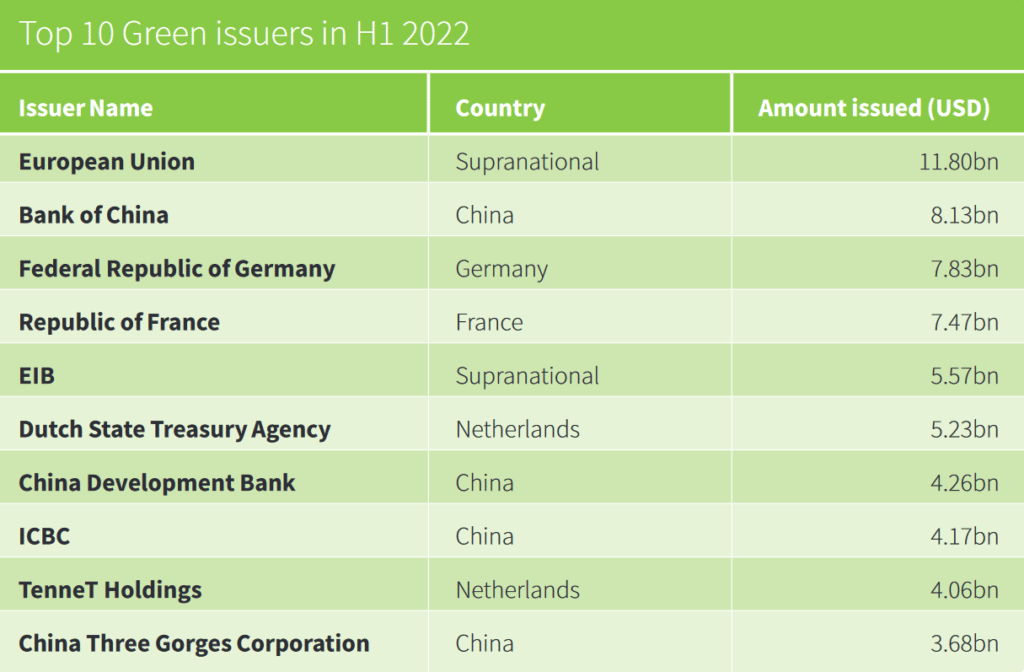

The most active issuers of green bonds in the first half of 2022 were the EU, China and the US. South Korea and Japan are other Asian markets enjoying notable growth.

The Two Sides of Sustainable Financing Instruments

Sustainable financing instruments provide the perfect platform for state and non-state actors to attract funds for climate-aligned projects. Furthermore, investors are willing to back all types of green projects – from slashing emissions in carbon-intensive sectors to building renewable energy capacity, improving energy efficiency and more.

Borrowers must follow green bond principles endorsed by International Capital Market Association. However, due to regulatory loopholes and a lack of proper supervision in many jurisdictions, sustainable financing instruments are also the perfect stage for greenwashing and exploiting investors’ trust.

Transition and Green Bonds Success Stories

Be it flood-prone regions suffering from rising sea levels or areas with continuous heatwaves, many countries across Southeast Asia are issuing green bonds to promote eco-friendly projects.

Thailand, for example, started issuing sustainability bonds in 2020 to fund its post-pandemic recovery. Furthermore, part of the proceeds will help lessen the persistent traffic problems and the substantial air pollution in Bangkok.

Singapore uses bonds for rail infrastructure development to stimulate the population to reduce its reliance on cars. Through such initiatives, the government hopes to slash land transport emissions by 80% around mid-century. Singapore also uses green bonds for climate change adaptation initiatives, including coastal protection.

The country has published a governance framework to make sovereign green bond issuance more transparent. It covers areas like the use of proceeds, project eligibility evaluation criteria, capital management and post-issuance allocation, results reporting and more. Going forward, the country plans to establish a green taxonomy, allowing investments to be aligned on an environmental impact basis.

In 2021, the Philippines launched its Sustainable Finance Roadmap to address climate change. The framework paved the way for the country’s first green bond issuance this year. The 25-year green bonds churned out USD 1 billion, highlighting the strong amount of investor confidence in the country’s decarbonisation and climate change mitigation efforts.

Other Southeast Asian nations like Malaysia and Indonesia are using green bonds for decarbonisation activities and financing the construction of large-scale solar power plants.

The Greenwashing Concerns with Transition and Green Bonds

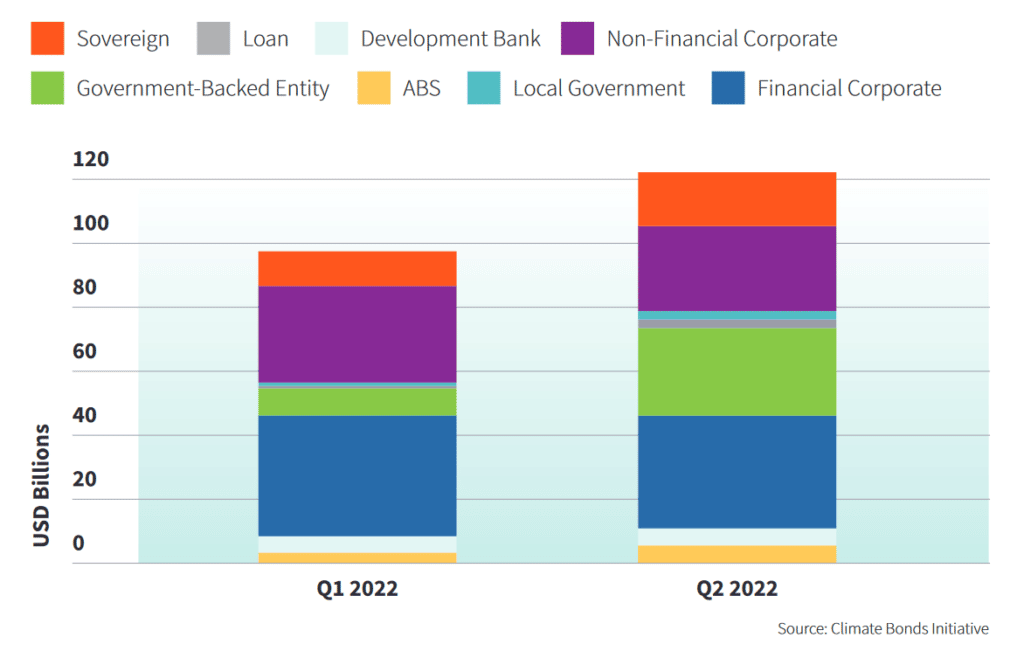

In H1 2022, green bond volumes came mainly from the private sector, continuing a trend from past years.

According to CBI, eight new issuers from China and eight from Japan were among them. All of them were from heavy-industry sectors, such as chemicals, steel, aviation, and utilities.

Japan

Energy Tracker Asia has previously covered the controversial use of proceeds from the transition bond programmes of JERA and Tokyo Gas. JERA, which is the country’s leading corporate CO2 emitter and is responsible for 15% of Japan’s total annual emissions, plans to fund ammonia and hydrogen co-firing projects. Such plants can release large amounts of nitrous oxide (NO2), a 298 times more potent polluter than CO2. Additionally, Tokyo Gas intends to support the development of LNG and grey hydrogen plants through its transition bonds programme

The case of JERA, for example, has made CBI express its opposition to combustion plants, which don’t align with the Paris Agreement’s goals. Furthermore, the organisation urged JERA’s management to reframe its transition plans around net-zero targets, including increasing the share of clean energy power. Currently, renewable energy accounts for just 1% of JERA’s total capacity.

These cases highlight a problem on a broader level. Experts consider existing green financing regulations in Japan imperfect. More specifically, the guidelines make it clear that the market, not authorities, should evaluate how “green” a fundraiser’s actions are. This allows the state and corporations to continue pouring supposedly green capital into fossil fuel-related projects.

China

In 2019, China was found to have provided USD 1 billion in “green” finance to coal projects. While the number of such instances on the state level has been reduced since then, the case isn’t the same on the corporate level.

For example, some green bond issuing companies have been repeatedly accused of water pollution and ecosystem degradation. Furthermore, there is also the infamous case of the green-bond-financed Hong Kong airport threatening the nearly extinct Chinese white dolphins.

The differences in existing green bond regulations in the country are leaving loopholes for greenwashing practices.

The Urgent Need For Regulatory Changes

Without proper policy backing, sustainable financing instruments can serve as a weapon for greenwashing. This risks eroding investors’ trust and losing out on capital, which is vital for the global net-zero transition and the fight against climate change.

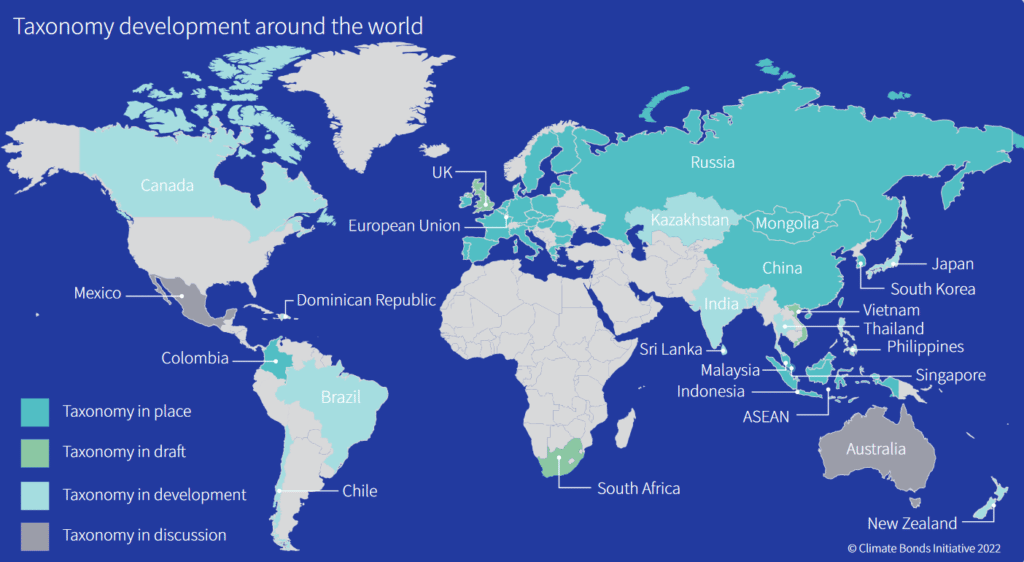

Currently, the EU is the leader in green taxonomy, which only covers activities that are unconditionally green. The EU standards are a benchmark for other countries to aim for. However, so far, similar policies are lacking across Asia.

Compared to the EU, ASEAN countries still rely heavily on fossil fuels. Due to this, the need for quick regulatory changes that safeguard the interests of green investors is even more pressing. At the end of 2021, the ASEAN put forward its own taxonomy to prevent greenwashing practices and better clarify what technologies are “green”. However, taxonomies in most Asian countries are substandard. Furthermore, the CBI report concludes that the EU aside, none of the taxonomy development approaches allow making the most out of the opportunities that transition finance and its tools open up.

Going forward, experts believe that taxonomies in fossil fuel-dependent regions will be more likely to brand natural gas as sustainable. Unless Asian countries develop ambitious green taxonomies that eradicate the greenwashing risk – or if the EU’s green bond standards grow into a de facto global standard – global decarbonisation, climate adaptation and mitigation efforts will underperform.

by Viktor Tachev

Viktor has years of experience in financial markets and energy finance, working as a marketing consultant and content creator for leading institutions, NGOs, and tech startups. He is a regular contributor to knowledge hubs and magazines, tackling the latest trends in sustainability and green energy.

Read more